2025: The deliberate massacre of Syria’s Druze

This article was written as part of an investigation into crimes committed in Suwayda during July 2025. It reflects only some of the findings and will be updated at a later date. For more information, visit the page dedicated to our investigation project: https://interstices-fajawat.org/our-projects/investigation-project/

Between July 13 and 21, 2025, the Syrian province of Suwayda in southern Syria was subjected to military aggression by armed groups affiliated with the Syrian de facto authorities, resulting in the deaths of more than 930 civilians and 550 Druze and Christian fighters. While this operation was widely presented as an intervention aimed at restoring order following inter-communal clashes, an in-depth analysis of the causes and circumstances of these events reveals a very different reality and highlights the full responsibility of Ahmad al-Sharaa’s non-elected government in what must be considered a war crime.

Context

On December 9, 2024, the day after Bashar al-Assad fled to Russia, Ahmed al-Sharaa (nom de guerre: Abu Mohammad al-Jolani) proclaimed himself head of the Syrian state, categorically rejecting any form of power sharing, decentralization, or federalism, while demanding that all armed groups lay down their arms and join the new national army, placed under the command of dozens of Islamist warlords appointed at the end of December to the highest positions in the army, including several foreign jihadists.

Along with the Kurds, the Druze are the only communities in Syria that enjoy both a form of autonomy within a specific territory and significant armed forces dedicated to the self-defense of their community on ethno-confessional or political grounds. For Al-Sharaa, their subjugation is therefore an important power issue, as only their total surrender can secure his control over the entire Syrian territory. During the first half of 2025, the de facto government proceeded methodically to achieve this goal.

As we publish these lines, the provinces of Deir ez-Zor and Raqqa have been almost entirely retaken by government forces and Bedouin armed groups, while the fate of the province of Hasakeh remains suspended pending the outcome of talks between the government and Kurdish forces. Consistent reports also suggest that US diplomacy is supporting the Syrian government in its efforts to bring the province of Suwayda under its control. It cannot therefore be ruled out that a new deployment of force may take place in the coming weeks.

First phase: negotiations and seeds of discord (January–March)

On January 1st, 2025, a first convoy from the General Security attempted to enter the province of Suwayda without prior coordination with local authorities and factions, who refused them access. The Druze position was very clear: there can be no armed deployment in the province and no disarmament of local factions in the absence of a state, a constitution, and a government, and therefore a minimum of democratic guarantees and concrete commitments to the protection of minorities.

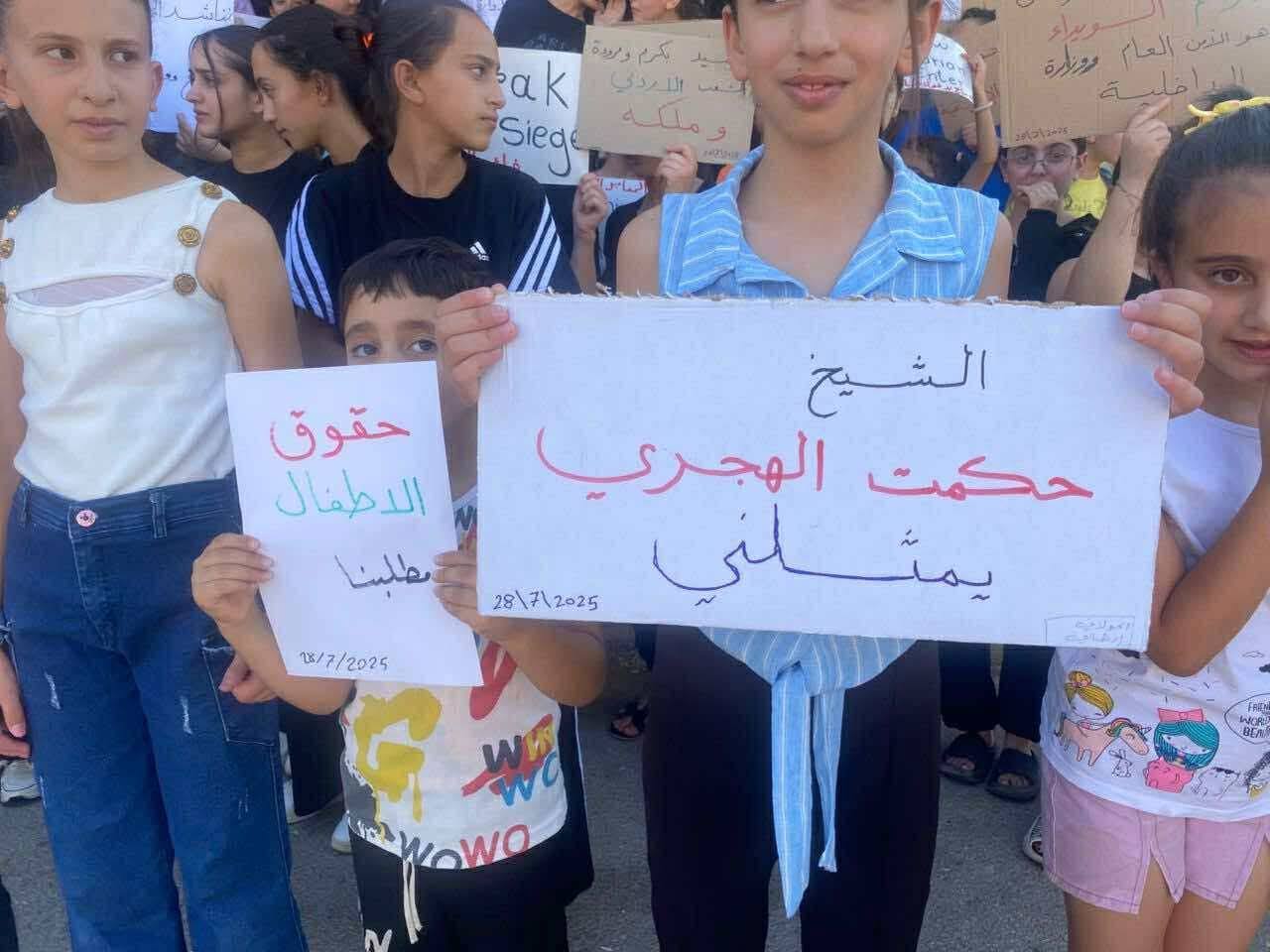

This event prompted one of the three main Druze spiritual leaders (Sheikh Aql or sheikhs of reason) in Syria, Sheikh Hikmat al-Hajari, to clarify his position in two interviews with Syria TV and 963+ on January 8. He shared his vision for the future, calling for national unity and inclusive, decentralized governance within the framework of a civil state. In particular, he emphasized that Suwayda had spoken out against separation since the beginning of the 2011 uprising. His position appeared relatively moderate and echoed that of many Syrians, although his leadership is far from consensual within the Druze community of Suwayda, particularly because of his support for Bashar al-Assad until 2023. It should also be noted that he has been in open conflict for more than twelve years with the two other sheikhs of reason, Youssef Jarbou’a and Hammoud al-Hennawi.

In the first quarter of 2025, rallies continued in Suwayda’s Dignity Square, where they had been held regularly since the fall of 2023 in opposition to the Assad regime. By now, these demonstrations were an opportunity to celebrate the fall of the regime and engage in heated discussions about the future. While opinions were divided, particularly on the trustworthiness of Al-Jolani and his armed forces, the majority of participants expressed hope and joy, singing songs of the 2011 insurrection and waving almost exclusively the Syrian independence flag with three red stars, which had once again become the official flag of Syria.

The divide within the Suwayda community widened in February, as the central government held direct negotiations with certain local factions, notably the two controversial Druze sheikhs Laith al-Balous and Suleiman Abdul Baqi, to prepare for the activation of the Ministries of Interior and Defense in Suwayda. Leaders of the micro-factions Madhafeh al-Karameh (Guesthouse of Dignity) and Ahrar Jabal al-Arab (Free Men of the Arab Mountains), the two men have had a troubled history over the past ten years, straddling the line between armed rebellion and banditry. The first, son of the very popular founder of the Rijal al-Karameh (Men of Dignity) movement, Wahid al-Balous, was expelled from the movement in 2016 after his father’s death due to his lack of integrity (cases of theft and handling stolen goods), before seeking his place in several factions and finally isolating himself and establishing his own. The second was convicted in 2009 for murdering the young Christian Moses George Francis in an honor killing, before becoming a member of the National Defense Forces, the main pro-Assad militia, and then specializing in mediating kidnapping cases, his role as an intermediary allowing him to take a percentage of each ransom. Both men rose to prominence during the war against gangs that began in 2022, during which Laith al-Balous was seen executing several members of Raji Falhout’s gang, a mafia boss close to Hezbollah and Bashar al-Assad’s military intelligence, in a public square (Dawar al-Mashnaqa). The images of this summary execution would later be manipulated to legitimize the violence committed against the Druze in 2025.Nevertheless, Al-Balous and Abdul Baqi regularly appeared in close company with senior government officials between February and April, and began to publicly advocate for the integration of factions into the national army, despite any coordination with all armed factions and components of local civil society. It should be noted that only the Rijal al-Karameh and Liwa al-Jabal (Mountain Brigade) factions—which at the time represented the majority position of Suwayda residents—coordinated with other civilian and armed components of the Druze community. During the same period, Colonel Bunyan al-Hariri, commander of the Syrian Army Division covering the three southern provinces of Syria (Suwayda, Deraa, Quneitra), visited armed groups in the neighboring province of Deraa to organize their integration into the national army. On February 19, he visited the Bedouin tribes of the Al-Lajat region, located between Suwayda and Deraa and known to be one of the strongholds of the Islamic State in the region. This area and its residents would play a key role in the July offensive.

In the days that followed, former officer Tareq al-Shoufi officially announced the existence of the Suwayda Military Council, which since December had been bringing together former military personnel and members of factions opposed to the government of Ahmad al-Sharaa and to integration into the national army. Stating its desire to establish a national army that is independent of all foreign influence and inclusive of all ethnic and religious groups, the movement was hoping to unite all Druze factions behind a single banner promoting secularism and federalism, based on the model of the Syrian Democratic Forces in northeastern Syria. A number of small local factions loyal to Sheikh Hikmat al-Hajari pledged allegiance to the Military Council in the weeks that followed, although the sheikh’s support for the Council has not been confirmed at this stage. It should be noted that the Military Council’s interventions during the protests in Dignity Square appeared to be marginal provocations carried out by a small group of about 15 young men waving portraits of Sheikh al-Hajari and lacking any coherent political discourse. The Military Council was indeed rather poorly perceived, accused by many within the community itself of both bringing together former agents of Bashar al-Assad’s regime (“fulul”) and serving foreign interests. While it is true that former loyalists and gangsters have found shelter among these new rebel forces, this is not sufficient grounds to accuse either faction of embodying a loyalist force as such, as is the case with the “Coastal Shield” brigade led by former Alawite officers.

On March 1, 2025, government forces arbitrarily set up a checkpoint at the entrance to the predominantly Druze neighborhood of Jaramana, located on the southeastern outskirts of Damascus, prompting the Druze factions to set up a checkpoint nearby in response. Armed individuals affiliated with the Ministry of Defense then attempted to pass through the druze-maned checkpoint and were asked to surrender their weapons, provoking an altercation followed by a shootout that resulted in the death of one of them and the capture of a second, who was wounded in the shooting. The situation then escalated during an argument between officers from the Jaramana-Salmiyah police station and community representatives, resulting in the expulsion of the officers and the seizure of weapons from the police station. Laith al-Balous finally stepped in as a mediator to calm the conflict, while Israeli officials added fuel to the fire by threatening the Syrian government with military intervention if the Druze were to be targeted.

Immediately after these incidents, a small group in Suwayda took the initiative to raise an Israeli flag at the entrance to the city and broadcast a video statement calling for Israeli intervention, before local factions took down and burned the flag. The local controversy over the flags—revealing an increasingly polarized debate within the province over the attitude to adopt toward the central government—only intensified in the weeks that followed. On March 6, the Rijal al-Karameh movement announced in a statement that it had reached an agreement with the government through Laith al-Balous and Suleiman Abdul Baqi to reactivate the security forces in the province of Suwayda. Eight General Security vehicles were delivered that same day, further fueling controversy within the community, with some factions threatening to burn the vehicles if they were deployed in the province.

It was at this point that the massacres of the Alawite population on the Syrian coast took place, resulting in the killing of more than 1,400 civilians, an event that cannot be separated from what would happen later in Suwayda. It should be mentioned in this regard that Bedouin tribes have already been used in these events by the government to act as auxiliary forces and compensate for the weakness of the army following Israel’s destruction of all the heavy weaponry left behind by the former regime. As well, sectarian hate speech, images of atrocities, and terror spread on social media and gradually took precedence over rational analysis of the situation. Hundreds of students from Suwayda were repatriated from university dormitories in Latakia and Tartus when the curfew imposed on the region was lifted. This evacuation operation was organized in particular through the intermediary of Suleiman Abdul Baqi, revealing the government’s desire to impose him as a mediator and legitimate guarantor of the protection of the Druze, despite his deplorable reputation in Suwayda. On March 8, he escaped an assassination attempt when his house was targeted by an RPG rocket.

During the second week of March, with the massacres committed on the Syrian coast still fresh in everyone’s minds, the government announced the signing of an agreement with Kurdish officer Mazlum Abdi for the integration of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) into the national army, while the government envoy to Suwayda, Mustafa Bakour, agreed with the Druze leadership to activate government forces in the province, on condition that its members be recruited exclusively from within the local community. Sheikh Hikmat al-Hajari initially gave his agreement in principle—his nephew and spokesman Usama al-Hajari was among the signatories of a memorandum adopted on March 12—before declaring that he himself had not signed the document and accusing the government of being a terrorist entity in a video broadcast from his guesthouse in Qanawat. That same evening, his supporters raised the Druze unitarian flag at several roundabouts in the city of Suwayda and fired shots into the air to boast about their opposition to the use of the independence flag and submission to the central government.

At the same time, the Rijal al-Karameh movement opened a recruitment office in Mazraa in collaboration with Laith Al-Balous, enlisting nearly 800 members of Bedouin tribes. In parallel, nearly 4,000 former members of Assad’s security forces had their status settled. Throughout March and April, numerous talks and meetings took place between civic, religious, and military leaders in Suwayda, as well as with Governor Mustafa Bakour, during which the druze side reiterated its refusal to disarm local factions without serious security guarantees for minorities, as well as its agreement to the deployment of security forces affiliated with the central government, once again on the sole condition that its members be exclusively from the province.

On April 20, Culture Minister Mohammed Yassin Saleh, Ahmad al-Sharaa’s brother Jamal, and Sayf ad-Din Bulad, commander of the 76th Military Division, met with several Bedouin leaders formerly affiliated with the Assad regime, including Ibrahim al-Hafel (Uqaydat tribe) and Farhan al-Marsoumi (Marsama tribe) at the latter’s home on the outskirts of Damascus (Al-Moadamiyeh). This controversial visit was part of a series of negotiations and bribing involving Bedouin tribes with the aim of securing their allegiance. These tribes will play a decisive role in subsequent events.

Second phase: first warning and intimidation (April–June)

On April 27, a fake recording was circulated on social media in which an unidentified voice could be heard insulting the Prophet Muhammad, sparking a riot by Islamists at the University of Homs, led by petroleum engineering student Abbas Al-Khaswani. This Islamist agitator, identified as one of the armed perpetrators of the attacks on the Syrian coast two months earlier, delivered an inflammatory speech in which he called for violence against the Druze, Alawite, and Kurdish communities. Following this speech, dozens of people chanting sectarian and hateful slogans stormed the university campus and attacked non-Muslim students. The elderly Druze sheikh Marwan Kiwan, accused of being the author of the recording, quickly denied the accusation, while the de facto authorities in Damascus issued an unconvincing press release thanking the rioters for their efforts to defend their prophet, instead of holding them accountable for the dangerous unrest they had caused. Abbas Al-Khaswani was not arrested and returned to the university the next day, where he and his colleagues would continue to threaten the safety of other students.

Two days later, the authenticity of the recording was finally denied by the government, but it took no action to prevent subsequent events from unfolding. As a result, unidentified armed groups attacked the Jaramana neighborhood that same day, targeting its residents and local Druze self-defense factions. The General Security intervened alongside the groups that had previously attacked the neighborhood, themselves identified as Bedouins from the Al-Uqaydat tribe, originally from Deir Ez-Zor, so that it was uneasy to distinguish between them. Seventeen attackers were killed before being reported as members of the General Security, while local factions were designated as the main instigators of the clashes.On April 30, armed Islamist groups from Dera’a, Deir Ez Zor, and Ghouta attacked the towns of Sahnaya and Ashrafiyeh-Sahnaya in a pattern similar to that seen in Jaramana, targeting residents and local Druze self-defense factions. This time, 45 people were killed, most of them members of the Druze community. Among them, 10 civilians were summarily executed, including the mayor of the city, Hussam Warwar, and his son Haider. Although Warwar had been seen welcoming General Security forces a few hours before his execution. At the same time, Druze factions from Suwayda attempted to leave the governorate to rescue their community under attack in Sahnaya-Ashrafiyeh, but were ambushed near Braq, on the road to Damascus, by mixed groups of local tribes and Islamists from Dera’a and Deir Ez Zor, as well as members of the General Security. A video clearly shows them opening fire as they stand side by side. As a result, 42 Druze fighters were killed, with the community of Salkhad particularly affected, with 11 martyrs belonging to the Quwaat Sheikh al-Karami and Quwaat al-‘Alya self-defense factions, including the leader of the latter, Amjad Baali.

On May 1, the central authority in Damascus reiterated its pressure on the leaders of the Druze community to accept the disarmament of local factions, unjustly accused of being the source of the unrest. Israel took advantage of the situation to threaten Syria and bombed near the presidential palace in Damascus, allegedly to “send a warning” to the Syrian authorities in case of threats against the Druze. Following negotiations between the government and the Druze leadership, a five-point agreement was finally adopted, providing for the activation of the police and General Security in the governorate of Suwayda, on condition that its members all originate from the region, as well as the securing of the road to Damascus and a ceasefire in all areas affected by the clashes of recent days. It should be noted that during the day, Laith al-Balous escaped an assassination attempt while traveling in Shahba, before being heckled in his town of Mazraa for opening it up to several General Security vehicles. The latter were once again sent back out of the province.

On the night of May 1, mortar shells were fired at the towns of As-Sawara al-Kbira, Al-Thaala, Ad-Dour, ‘Ira, Kanaker, and Rsas in the province of Suwayda. All factions in Suwayda, comprising more than 30,000 fighters, were put on alert and deployed to strategic points throughout the governorate, while the General Security encircled the governorate that same evening, ostensibly to prevent any further attacks from Dera’a. This did not prevent armed groups from attacking the villages of Lubayn, Harran, Ad-Dour, and Jreen, located on the western border of the province, where they encountered strong resistance, resulting in the death of most of the attackers. The number of casualties is unknown, but the attackers were identified as belonging to local Bedouin tribes.

On May 2, an Israeli drone flying over Suwayda targeted a farm in Kanaker, killing four of its Druze inhabitants. One of them, Issam Azam, was known for actively supporting the protests in Dignity Square against the Assad regime. During the night, Israeli planes launched a series of strikes on military sites in Dera’a, Damascus, and Hama. On May 3, Khaldun Sayah Al-Mahithawi, a Druze lawyer involved in negotiating the release of another lawyer kidnapped north of Suwayda, was assassinated in Aqraba, near Jaramana, while the 11 martyrs of Salkhad were buried after a ceremony attended by thousands of people in their hometown.

On May 5, clashes between Bedouin tribes and Druze factions continued in the vicinity of al-Thaala and Harran in Suwayda, while rumors circulated that Druze factions were threatening mosques. Several imams from the region and representatives of local Bedouin tribes denied these rumors of sectarian threats by the Druze against Muslims, reaffirming peaceful coexistence within the governorate and the need to combat fake news and sectarian incitement on social media. The Druze factions have in fact deployed to protect Muslim religious sites from any individual sectarian initiatives. After the General Security withdrew from the town of As-Sawara al-Kbira, the Suwayda police entered the town accompanied by Governor Mustafa Bakur and found several houses burned and looted, as well as the Druze shrine. It should be noted that the only town where houses were looted and vandalized in Suwayda was also the only one where General Security forces had been deployed.

As part of the agreement signed on May 1, the government has set up several checkpoints on the road between Suwayda and Damascus, while Druze police officers have been deployed at the entrance to As-Sawara al-Kbira, the first village in the province. Eleven kilometers further north, at the strategic junction of the roads connecting Damascus, Suwayda, and Deraa, a checkpoint was entrusted to armed men belonging to Bedouin tribes in the region (the Al-Na’im tribe from the village of Al-Mtalleh and the Al-Lajat region), whose affiliation with government forces was uncertain: they were not wearing official uniforms and several of them were wearing masks and displaying ISIS symbols. At the same time, it was announced that three members of the Uqaydat tribe from Shuhayl (Deir Ez-Zor) had been appointed to senior positions: Hussein al-Salama as head of intelligence, replacing Anas Khattab; Amer Names al-‘Ali as president of the Central Control and Inspection Authority (anti-corruption); and Sheikh Rami Shahir al-Saleh al-Dosh as head of the Supreme Council of Tribes and Clans, an entity subordinate to HTS since 2019. These appointments came just as their tribe was one of the most involved in the deadly attacks against the Druze community in recent days.

Between May and July, numerous complaints were made about the Braq-Masmiyeh checkpoint, whose guards were accused of harassment, theft, and extortion against road users traveling to or from Suwayda. On several occasions, continuing criminal practices dating back to before the fall of the Assad regime, passengers were kidnapped or targeted by gunfire from armed Bedouin groups residing in Al-Mtalleh and Al-Lajat. As a result, the government’s May 1 commitment to secure the road between Damascus and Suwayda has not been honored and has been violated by members of the government forces themselves. During the same period, sectarian violence has increased, with members of religious minorities being murdered every week in different parts of the country, culminating in the attack on the Mar Elias Orthodox Christian Church in the Dweila neighborhood of Damascus on June 22, 2025. Five people from the Christian community of Kharaba, a village west of Suwayda, were among those killed in the explosion. It was later revealed that one of the attackers was a member of the Ministry of Defense.

Third phase: the invasion and massacres (July)

In early July, under the pretext of settling a dispute with the Bedouin groups in charge of the checkpoint, government forces interrupted road traffic for several hours, during which the security officials for Suwayda and Deraa, Ahmed al-Dalati and Shaher Jabr Omran (nom de guerre: Abu al-Baraa) traveled to Bedouin hamlets in the Al-Lajat region to reconcile two clans disputing control of the Braq-Masmiyeh checkpoint and offered to integrate several dozen of their members into the Interior Ministry forces.

On July 11, Druze merchant Fadlallah Dwara was kidnapped near the checkpoint, beaten, robbed of his vehicle, cargo, phone, and money, and then thrown onto the side of the road. The response was swift. The very next day, a Druze faction from Ariqa kidnapped Bedouins—who were not connected to Fadlallah Dwara’s kidnappers—prompting a retaliatory response from Bedouin clans in Suwayda, particularly those in the Al-Maqwas neighborhood, located at the eastern entrance to the city of Suwayda. At around 9 a.m. on July 13, they blocked the road to the mountains and kidnapped five Druze civilians.

1. The Southern Tribes Gathering starts the conflict

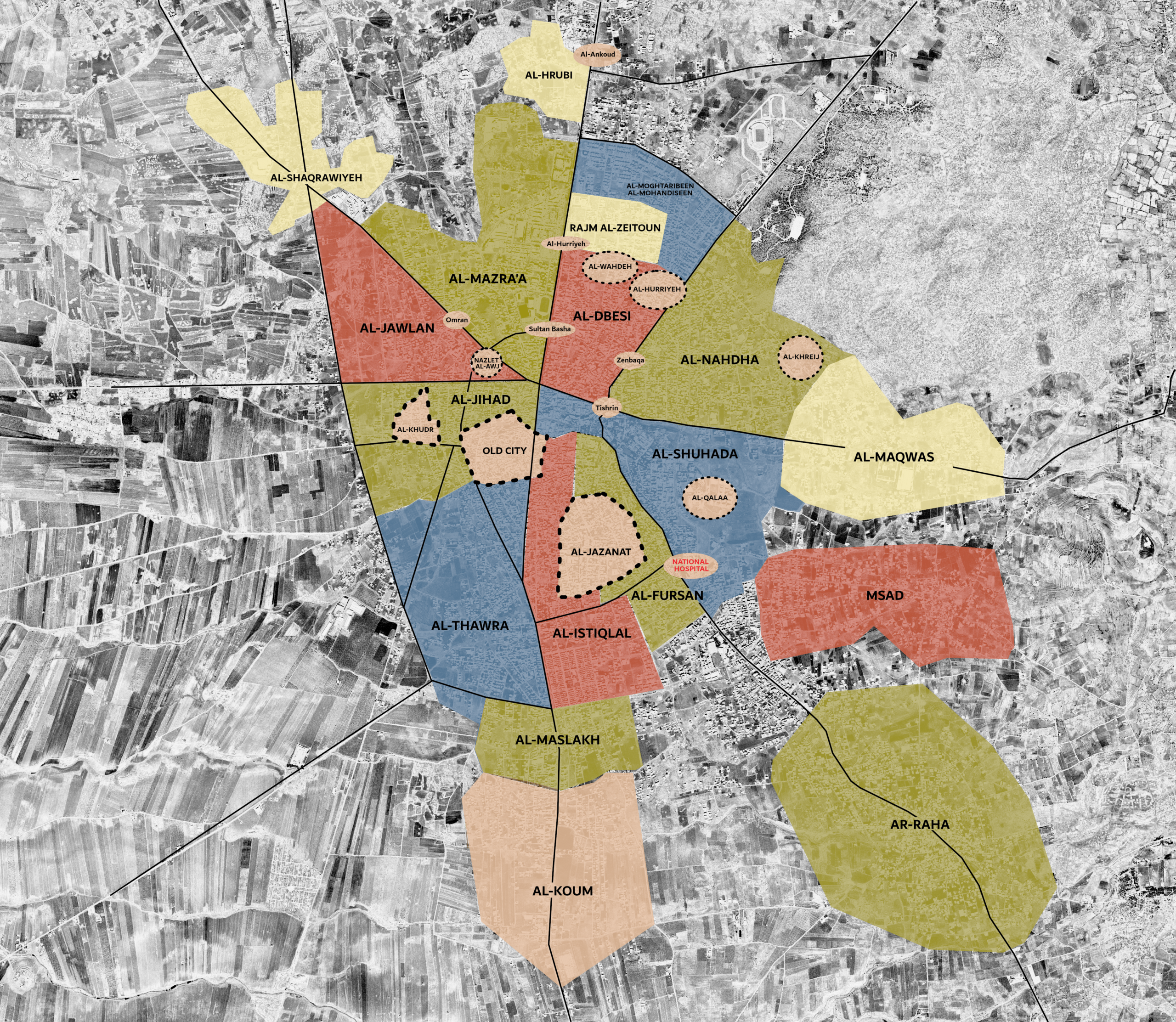

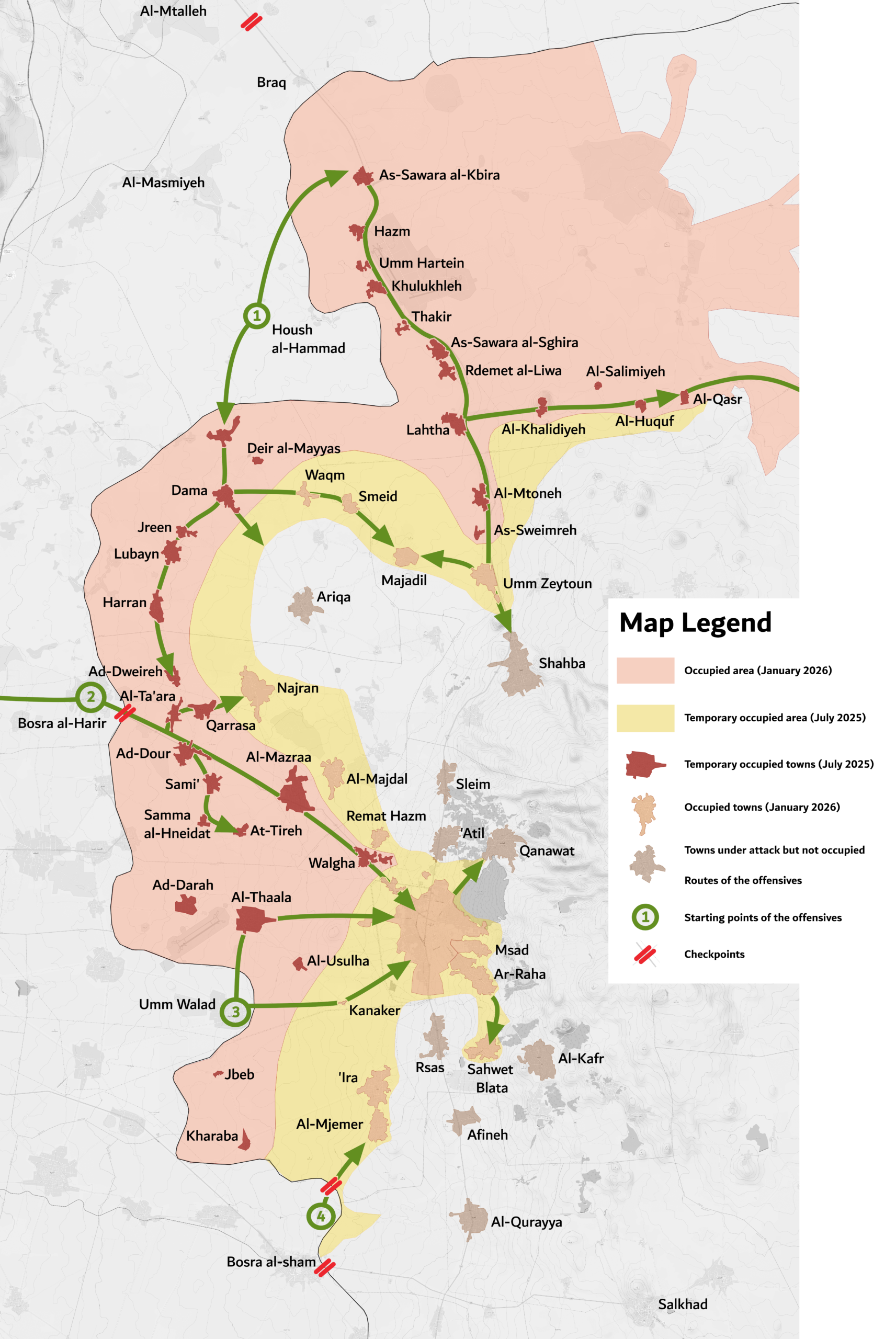

Al-Maqwas is a neighborhood that has been divided by conflicts between Bedouin clans for many years. The Al-Badah and Al-Kaniher clans, involved in drug trafficking, have ruled the area since they expelled the rival Al-Anizan clan in May. They are associated with the Southern Tribes Gathering, a local tribal confederation set up by a notorious drug trafficker, Sheikh Rakan Khalid al-Khudair, who lives outside Suwayda in Al-Mtaleh after going into exile in Jordan between 2019 and 2024. It was the latter organization, close to Suleiman Abdul Baqi and loyal to the government, that signaled the start of armed hostilities, provoking a response from the Druze factions. The latter laid siege to Al-Maqwas, trapping its residents inside and preventing the wounded from being evacuated to hospital. It was this blunder that allowed the Southern Tribes Gathering to spin a catastrophic and partially false narrative that would justify the intervention of government forces and the mobilization of Bedouin tribes throughout Syria in the hours that followed, in particular the narrative claiming ethnic cleansing of Bedouins by armed factions associated indiscriminately with the Suwayda Military Council and Sheikh Hikmat al-Hajari.The clashes initially extended to the Bedouin neighborhoods on the outskirts of Suwayda city (Rajem al-Zeytun, Al-Hrubi, Al-Mansoura, and Al-Shaqrawiyeh), where several armed groups began attacking Druze factions. Throughout the day, the wounded poured into the national hospital, which reported 54 wounded and 13 dead by early evening, including children and elderly people shot in the head by snipers, while the tribes reported 50 wounded and 10 dead on their side, including three women. Shortly after 4 p.m., a first attack from outside the province of Suwayda targeted the As-Sawara al-Kbira checkpoint (in the north of the province), manned by Druze members of the new local police force. An hour later, attacks targeted the neighboring village of Hazm, followed by coordinated attacks shortly before 7 p.m. against several villages in the west of the province from the Housh al-Hammad area in Deraa: Harran, Jreen, Lubeyn, Sami’, and At-Tireh. This was a clear sign that the Bedouin tribes of Hauran and Lajat (mostly affiliated with the Al-Na’im tribe) were behind the offensive.

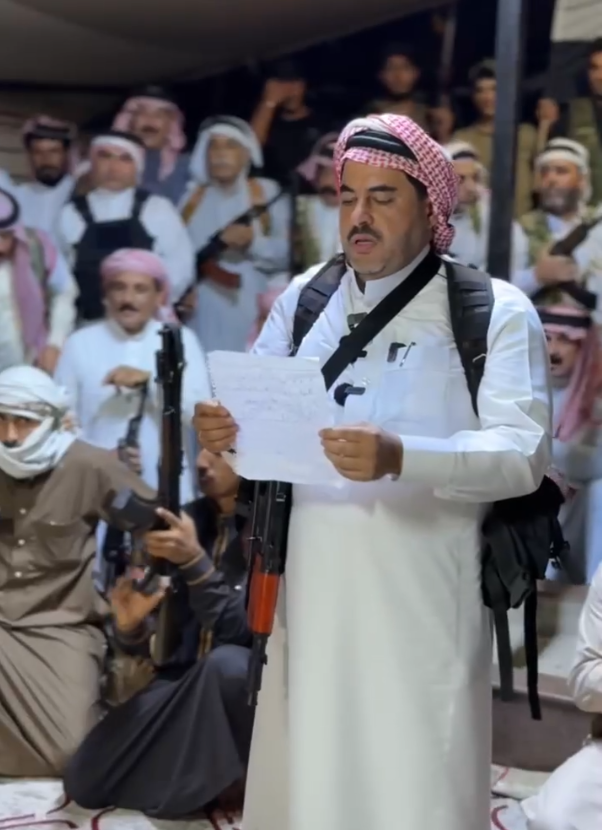

Alert issued by the Southern Tribes Gathering on July 13 at 4:18 p.m.

2. Government forces invade Suwayda

At this stage, negotiations had already begun under the mediation of Sheikh Youssef Jarbou’a in an attempt to resolve the conflict and secure the release of hostages on both sides. These negotiations culminated in the middle of the night with a commitment from both parties to release the hostages, but this did not stop the fighting. On the contrary, at around 1:30 a.m. on July 14, government forces occupied As-Sawara al-Kbira, while at 7:30 a.m. they entered the province from the west along the Bosra al-Harir–Mazraa and Umm Walad–Kanaker routes. The villages mentioned above were quickly occupied by the army after being taken by Bedouin tribes, followed by Ta’ara and Ad-Dour around noon, then Qarasa, Najran, at-Tireh, and Kanaker an hour later. The towns of Mazraa and Al-Thaala were taken between 3 p.m. and 4 p.m., while ‘Ira and Mjemer decided to open their gates to government forces. Everywhere, homes were looted, vandalized, and burned, while their occupants suffered indiscriminate violence at the hands of both tribes and government forces, even in villages that offered no resistance.

According to initial reports, the army units involved in the offensive against Suwayda belong to the following divisions:

- the 40th based in Deraa and commanded by Banyan Ahmad Al-Hariri (Abu Fares);

- the 42nd based in Palmyra and commanded by Mohammed Saeed Abdullah;

- the 52nd based in Homs and commanded by Haitham al-Ali (Abu Muslim Afs, Abu Muslim al-Shami)

- the 54th based in Homs and commanded by Hussein Abdullah Al-Obeid (Abu Suheib);

- the 62th based in Hama and commanded by Muhammad al-Jassem (Abu Amsha);

- the 70th based in Damascus and commanded by Essam al-Buwaydhani’s (Abu Hammam) deputy;

- the 72nd based in Aleppo and commanded by Doghan Suleiman;

- the 82nd based in Hama and commanded by Khaled Mohammed al-Halabi (Abu Khattab).

The head of military operations Hasan Abd al-Ghani announces the launch of the intervention, Bosra al-Harir, July 14, 6:30 p.m.

At least five of these divisions are led by (ex)-jihadists, while the 82nd Division contains elements likely to sympathize with ISIS. Several members of its units have been seen in videos in Suwayda wearing the organization’s emblem. A number of factors also confirm the presence of two units of the special forces with a notorious reputation: the Ali Bin Abi Talib brigade commanded by Abd al-Mun’im al-Dhaher (Abu Suleiman al-‘Iss) – who would get injured in the battle – and the “Red Bands” unit, whose leadership remains unclear to this day. The latter are trained by private military companies founded by foreign jihadists, notably Malhama Tactical, a group founded by Chechen Abdullah Tac. It should be pointed out that a Chechen fighter was taken prisoner by Druze factions, who interrogated him on camera.

In the middle of the afternoon, the Suwayda National Hospital announced that it had recorded 53 deaths and more than 200 injuries. While other towns in the province, such as Walgha, ‘Atil, Rima Hazem, and Rsas, were already being bombed and experiencing clashes, the advance of government forces was finally halted shortly before 6 p.m. when the Israeli air force carried out its first strike between Mazraa and Walgha, at the entrance to the University of Agricultural and Veterinary Studies, before following up with further strikes on other roads leading to Suwayda.

At dawn on July 15, intense military pressure combined with international diplomatic pressure forced Sheikh Al-Hajari to accept the deployment of government forces in the province and city of Suwayda and to call on the factions not to resist and to cooperate with them by handing over their weapons. Thus, at 8 a.m., Interior Ministry Colonel Ahmed al-Dalati announced the entry of government forces into Suwayda and the enforcement of a curfew, calling on Druze factions to lay down their arms. At 8:15 a.m., government forces entered the outskirts of Suwayda from Kanaker in the southwest, and thirty minutes later they reached the Omran roundabout in the northwest. Clashes broke out immediately afterwards and were quickly accompanied by acts of violence as armed groups with no clear affiliations spread throughout the city’s neighborhoods and proceeded to systematically destroy and loot shops and homes, as well as summarily execute numerous civilians.

At 10:50 a.m., an initial report already mentioned 24 executions of civilians, while at 12:20 p.m., news spread of the massacre of more than a dozen members of the Al-Radwan family in the guesthouse of their home, even as Ahmed al-Dalati had just declared a ceasefire with the aim of bringing the Druze leadership back to the negotiating table. Ahmad al-Dalati and Shaher Jabr Omran thus met around noon with representatives of various local religious groups and factions in the Druze shrine of Ain al-Zaman, located in the heart of the city, even as fighting and crimes continued to unfold in the surrounding neighborhoods.

An hour later, the first images of the atrocities were made public, while the attackers posted videos of their own crimes on social media in real time. Many videos show members of the government forces and Bedouin tribes staging scenes in which they beat civilians, forcibly shave their mustaches, and even summarily execute them before desecrating their corpses, calling them repeatedly “ya khanazir”, which means “you pigs!”. Entire families were executed in their homes or in public spaces, while many people were shot dead in their cars or targeted by snipers as they tried to flee the city. Among the victims were many elderly people and children. The youngest victim was three months old. They also left numerous inscriptions on walls, openly signing their names and claiming responsibility for their crimes. These numerous acts of violence were committed in most of the occupied neighborhoods of the city, even though a dozen journalists affiliated with the Ministry of Communication were present nearby, as well as Security Chief Ahmad al-Dalati, who appeared at around 2:20 p.m. on the roof of a vehicle in the middle of the Bedouin neighborhood of Al-Maqwas to announce its “liberation.”

Until dawn on July 17, government forces and their Bedouin auxiliaries fought with Druze factions for control of the city’s neighborhoods, while the Israeli air force carried out targeted strikes in and around Suwayda. The National Hospital neighborhood was the scene of intense fighting on several occasions over the two days: government forces targeted the hospital for the first time on July 15 at around 5 p.m., then again on the morning of the 16th, finally taking control of it at around 3 p.m. that same day. Members of the army and General Security killed the police officers in charge of security at the premises, then executed wounded patients and medical staff: CCTV footage shows the execution of nurse Mohammad Buhsas in the hospital lobby. When government forces began their withdrawal at dawn on the 17th, armed Bedouin groups remained in the city and were repelled or eliminated by Druze factions during the day. In several neighborhoods where they had remained over the previous 24 hours, numerous bodies of executed civilians were discovered.

Several sources confirm that on the morning of July 17, as Druze factions regained control of the situation, crimes were committed against Bedouin populations in several localities, who were subjected to forced expulsions, physical violence, and even killings, while a number of homes were set on fire. There are also indications that the Al-Hrubi mosque was vandalized, while satellite images confirm that destruction was carried out in Shahba and Breiki. Unfortunately, these localities remain inaccessible to independent investigators, and press reports of persecution against Bedouin populations are riddled with approximations and false testimony, making it impossible to distinguish truth from fiction.

3. The Syrian Council of Tribes and Clans comes to the rescue

On July 17 at around 3:30 p.m., the Southern Tribes Gathering launched an aggressive communications campaign, adding to its appeal to Bedouin tribes an appeal to the Sunni community as a whole, claiming that Druze factions were engaged in ethnic cleansing of Sunni tribes in Suwayda and were directly targeting mosques. The movement specifically accused Druze factions of kidnapping hundreds of Bedouins and committing atrocities against them. Photographs of Druze and Christian families executed in recent days were manipulated to suggest that the victims were Bedouins, while images showing Druze fighters desecrating the bodies of tribal fighters reinforced the idea that large-scale abuses were being committed against Bedouin civilians. In the wake of these incitements, the Syrian Council of Tribes and Clans, headed by Abdul Moneim al-Naseef, and the Army of Tribes, commanded by brother of above-mentioned Ibrahim Al-Hafel, Sami Al-Abdulaziz, brought together more than 40 tribes and clans from all over Syria to join the call and converge on Suwayda, while those still on the ground regained control of the villages from which government forces had withdrawn in the previous hours: Al-Mazraa, As-Sawara al-Kbira, Hazem, Ad-Dour, and Al-Thaala. On July 18 and 19, Bedouin tribes freely entered the province of Suwayda and gradually regained control of some fifteen villages north of Shahba, where they proceeded to loot and systematically destroy homes, while most of the residents still present were executed, particularly the elderly. Many women and children were kidnapped after their loved ones were murdered in front of them, while at least three cases of beheadings have been documented, as well as several cases of people being burned alive. Atrocities were also committed on the outskirts of Suwayda, where pockets of resistance from Bedouin groups present for several days persisted until July 20. These crimes were committed despite the ceasefire agreement discussed in the absence of Druze representatives and made public by White House envoy Tom Barrack on the night of July 18-19.

At around 1 p.m. on the 19th, government forces took over from the Bedouin tribes and began occupying the 34 villages that could not be liberated by the Druze factions. However, it was not until the evening of July 21 that the Bedouin tribes ceased their attacks on Umm Zeytoun, Shahba, Ariqa, and Majadel, during which a large number of Shaheen drones were used. From July 21, the government organized the evacuation of 1,500 Bedouin civilians to Deraa, representing less than 5% of the total Bedouin population residing in the province of Suwayda. At the same time, humanitarian aid convoys were sent to Suwayda as part of a communication campaign aimed at preserving the government’s image, which continued to present itself as a mediator in inter-communal conflicts and denied that its own armed forces had committed any crimes. When the Druze community collected the bodies, it was found that many Bedouin fighters were carrying cards identifying them as members of the Ministries of Defense and the Interior, while videos released by Druze factions alleged the presence of foreign fighters.

The head of the Council of Syrian Tribes and Clans Abdul Moneim al-Naseef calls on all Bedouin tribes to converge on Suwayda to reinforce the Southern Tribes Gathering, Deir Ez-Zor, July 18, 12:50 a.m.

At this stage of our investigation, it has been confirmed that the following Bedouin tribes and clans actively participated in the assault on the Suwayda community:

1. Anzah

2. Bakara

3. Bani Khalid

4. Bu Sha’ban

5. Fawa’ira

6. Jabur

7. Mawali

8. Na’im

9. Shammar

10. Tayy

11. Uqaydat

12. Abd al-Karim

13. Afadlah

14. Arida

15. Bani Sakhr

16. Breidij / Breij

17. Bu Issa

18. Bu Saraya

19. Damalkha

20. Dulaim

21. Fidaan

22. Hadadin

23. Hneidi

24. Hassoun

25. Huweidi

26. Haweitat

27. Ja’abara

28. Marsuma

29. Na’san

30. Omeirat

31. Rifa’ah

32. Ruwalah

33. Sakhani

34. Sarhan

35. Sardiya

36. Saba’ah

37. Sabeila

38. Shamur

39. Sharabin

40. Waldah

41. Zubayd

However, it cannot be ruled out that members of other tribes participated individually or collectively in the attack, as at least 40 other tribe and clan names were mentioned in our sources by participants and members of these groups themselves. This would bring the number of participating clans and tribes to 81, out of a total of 211 Syrian clans and tribes listed in our database, which would therefore represent between 38 and 40% of the country’s tribes and clans.

It is also important to remember, as we have already pointed out, that the government forces themselves have recruited Bedouins on a massive scale. Furthermore, the rebel and jihadist groups that merged with Hayat Tahrir al-Sham in January 2025 to place themselves under the command of the Ministry of Defense were already largely made up of Bedouins.

Fourth phase: siege and denial (July-present)

In the days following the ceasefire, journalists were kept out of the province, where government forces set up checkpoints and claimed that Druze factions were preventing anyone from entering, a claim refuted by a number of residents. The Civil Defense (“White Helmets”) organized a humanitarian corridor for people residing abroad from the south of the province to the neighboring town of Bosra al-Sham, until several incidents involving gunfire and passenger abductions interrupted operations.

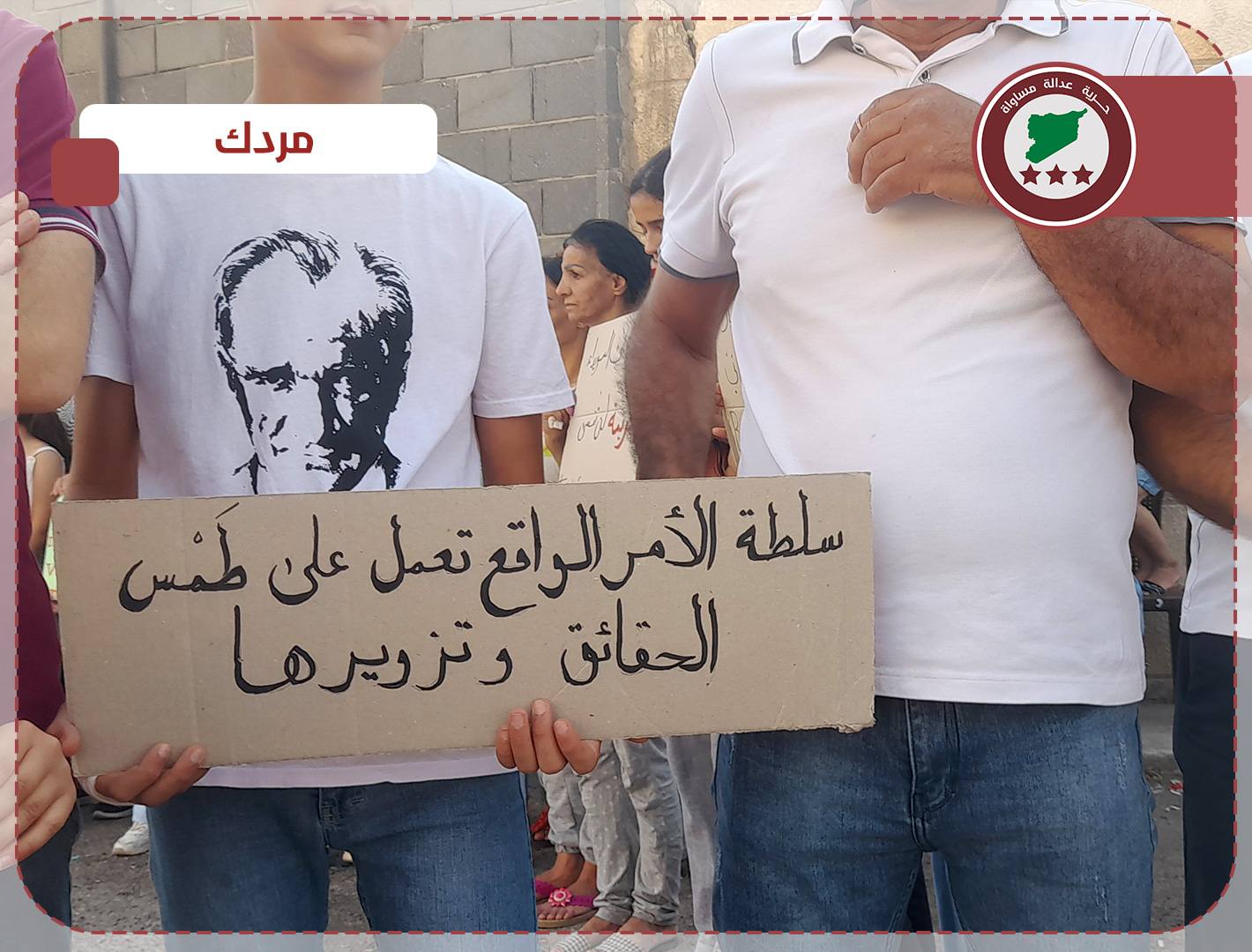

On July 31, the Ministry of Justice announced the establishment of an Investigation Committee on the events in Suwayda, but like other institutions implemented by the de facto authority, it does not meet the conditions of impartiality and independence required to carry out these investigations. The representative of the commission of inquiry into crimes committed against the Alawites on the Syrian Coast in march, Yasser al-Farhan, who delivered his conclusions the day after the massacres in Suwayda (July 22), had earlier thanked the Bedouin tribes for their intervention on the coast, while Anas Ayrout, head of the Supreme Committee for the Preservation of Civil Peace in Syria, issued a statement on July 18 praising the tribes and congratulating them on their mobilization. Another member of this committee, Sheikh Ragheb al-Saifi from the Uqaydat tribe, has been identified as one of the coordinators of the attack on Suwayda. Finally, Al-Sharaa himself thanked the tribes for their “heroic commitment” in his public address on July 19, without ever considering them to be “outlaw gangs” that needed to be disarmed.

On October 12, the government organized a campaign called “Suwayda is ours and we are hers,” an inappropriate charity event intended to raise money for the province. The event was held in the martyred village of As-Sawara al-Kbira, a Christian village whose church was burned down and many of whose residents were murdered, in the presence of Mustafa Bakour, representatives of the tribes involved in the massacres, and Laith al-Balous and Suleiman Abdul Baqi. The latter are portrayed by the government as representatives of the Druze community and are subsequently called upon in diplomatic negotiations abroad, even though they played an active role in committing crimes against their own community. Suleiman Abdul Baqi, who, it should be remembered, himself murdered a young Christian for religious reasons, was promoted to “Head of Security for Suwayda” before being invited to Washington by members of the US Congress on January 22, 2026.

On December 17, the leader of the Southern Tribes Gathering, Rakan al-Khudeir, organized his “Victory Festival” in his stronghold of Al-Mtalleh—the Bedouin village where the violence began—to celebrate the anniversary of Assad’s fall, declaring that the Southern Tribes’ allegiance to the state was a national duty. Mustafa Bakour and several government representatives were present, as well as representatives of the Council of Tribes and Clans.

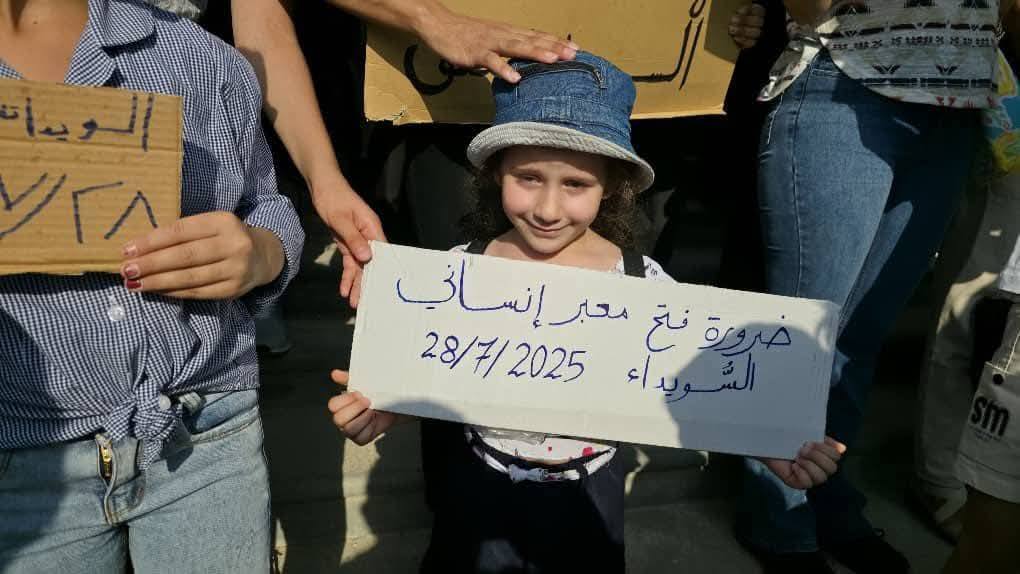

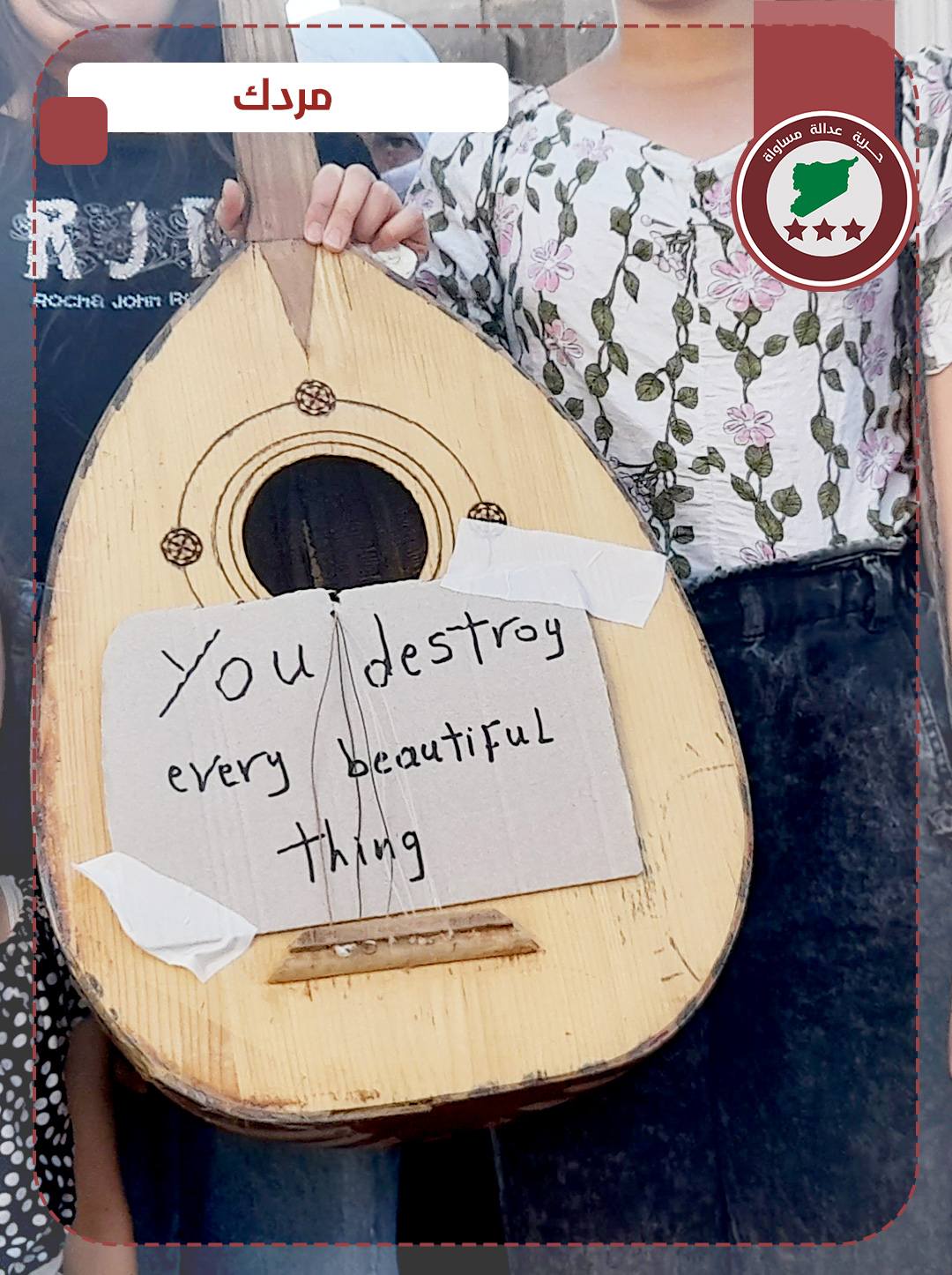

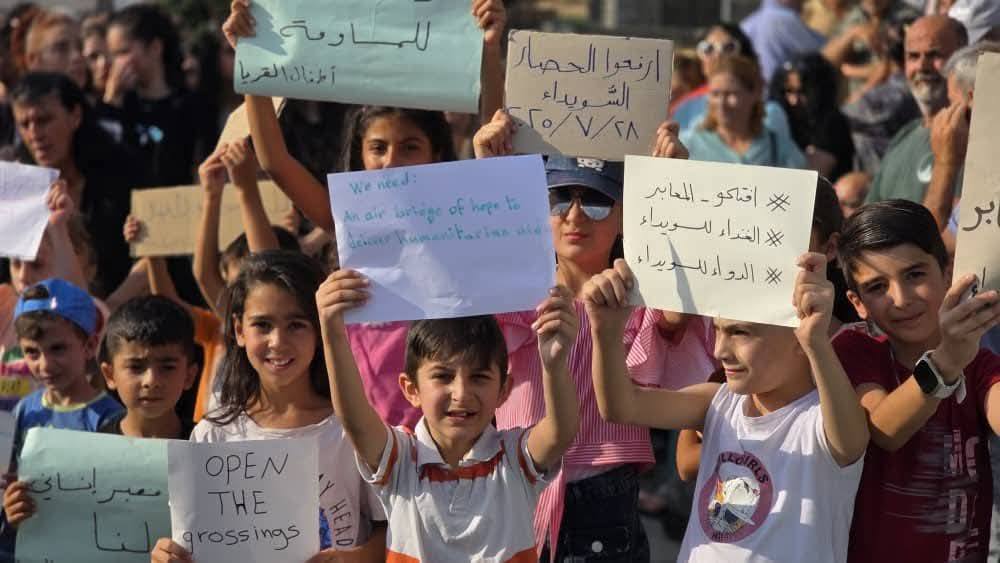

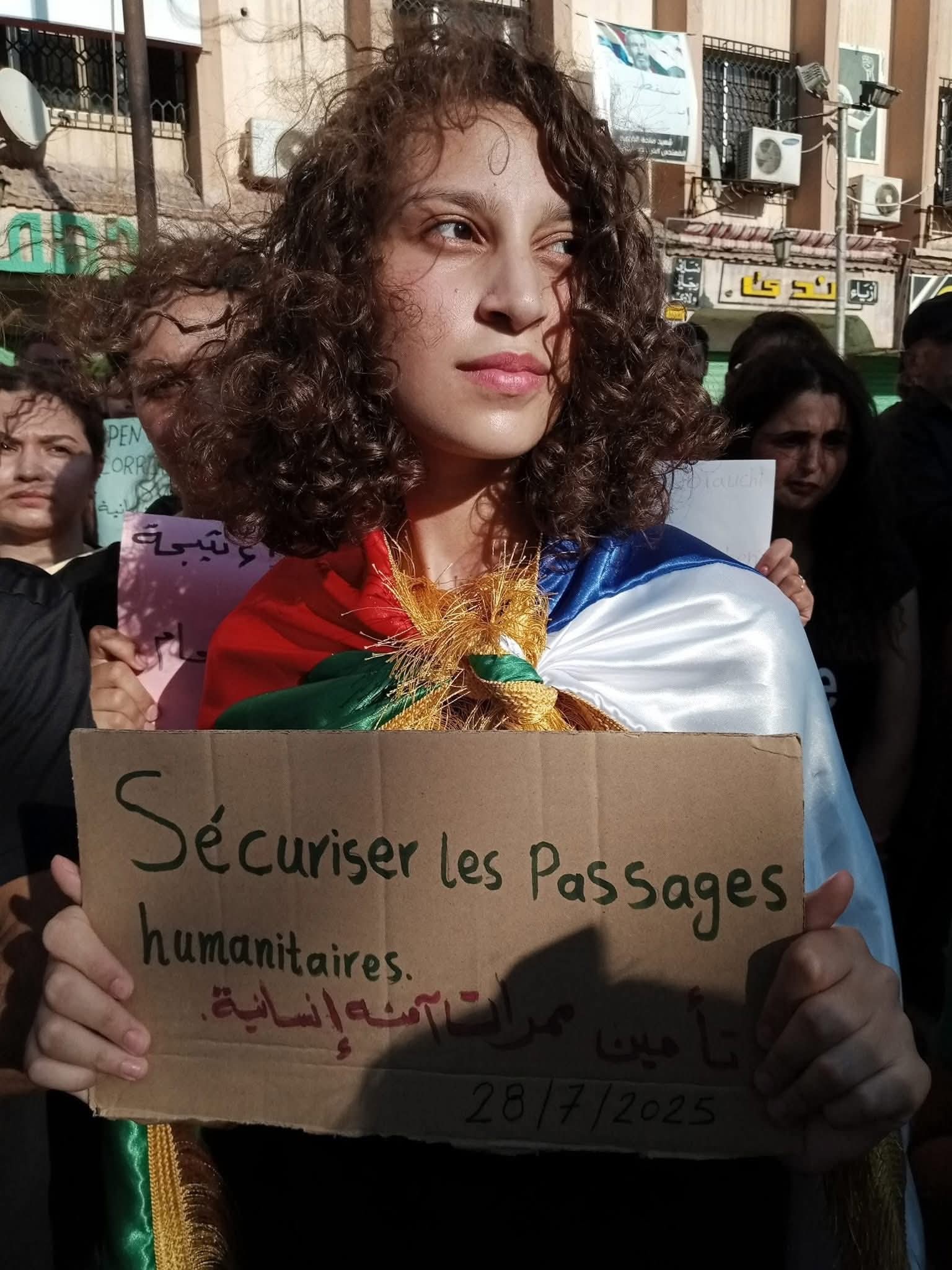

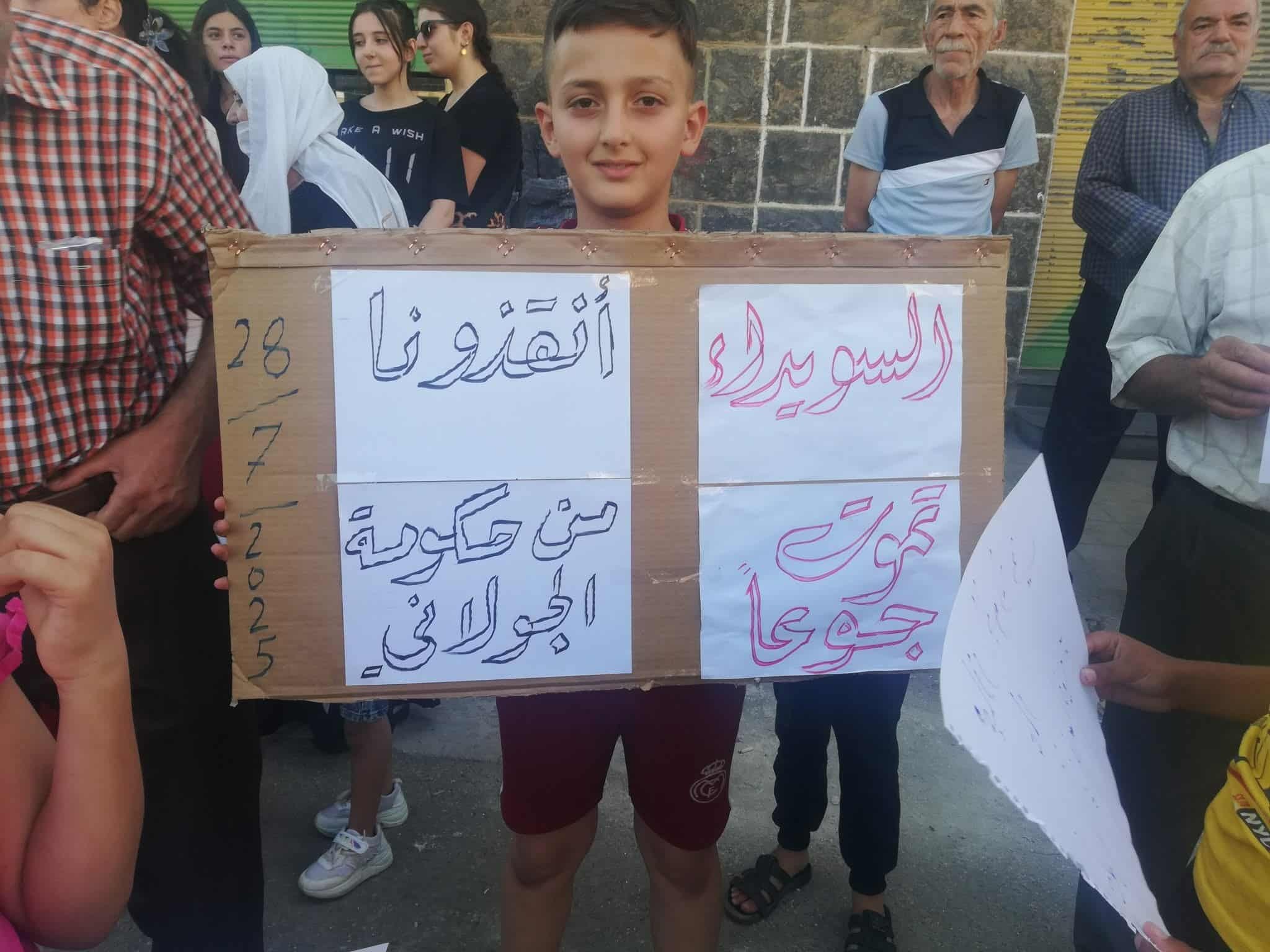

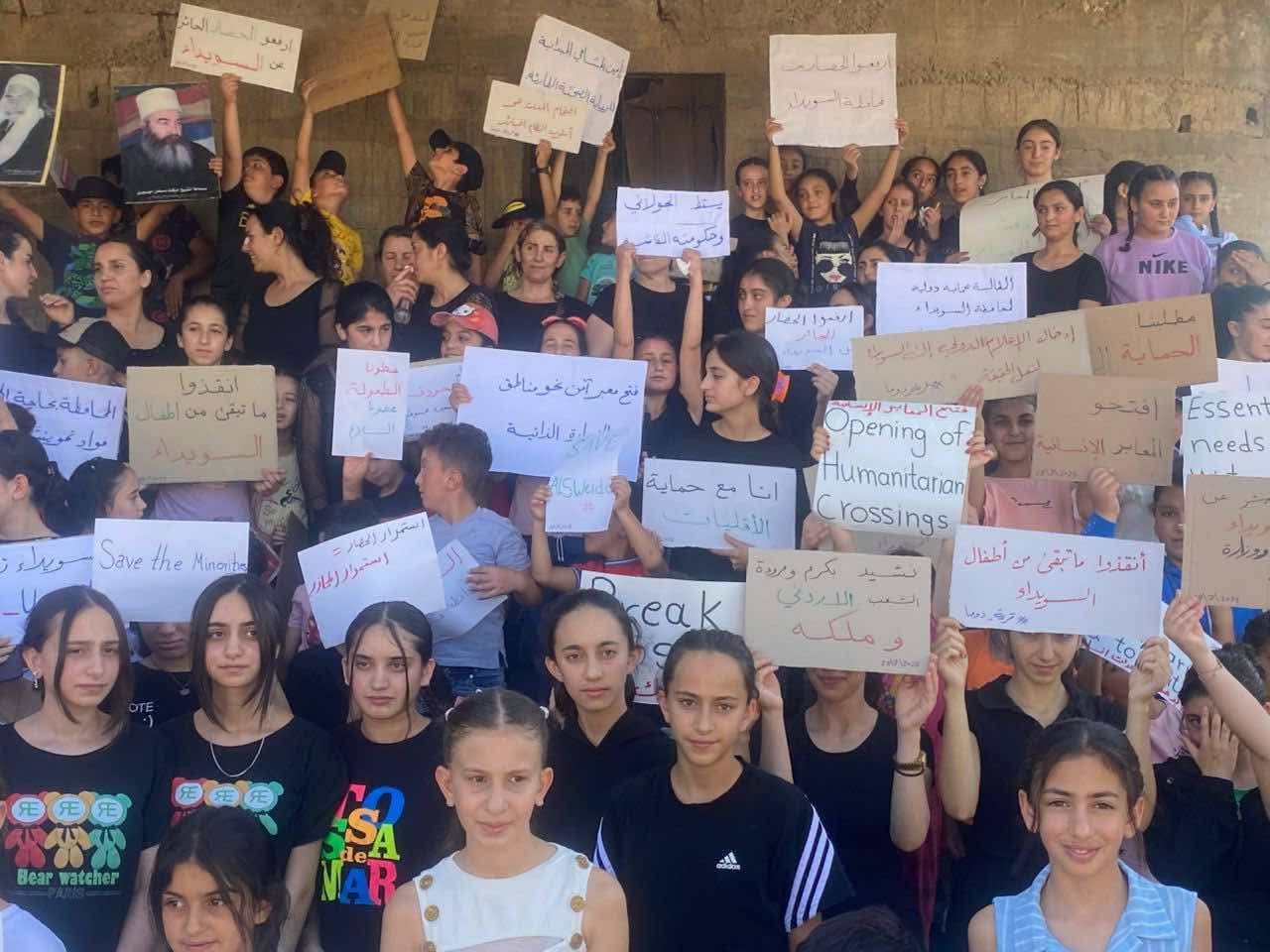

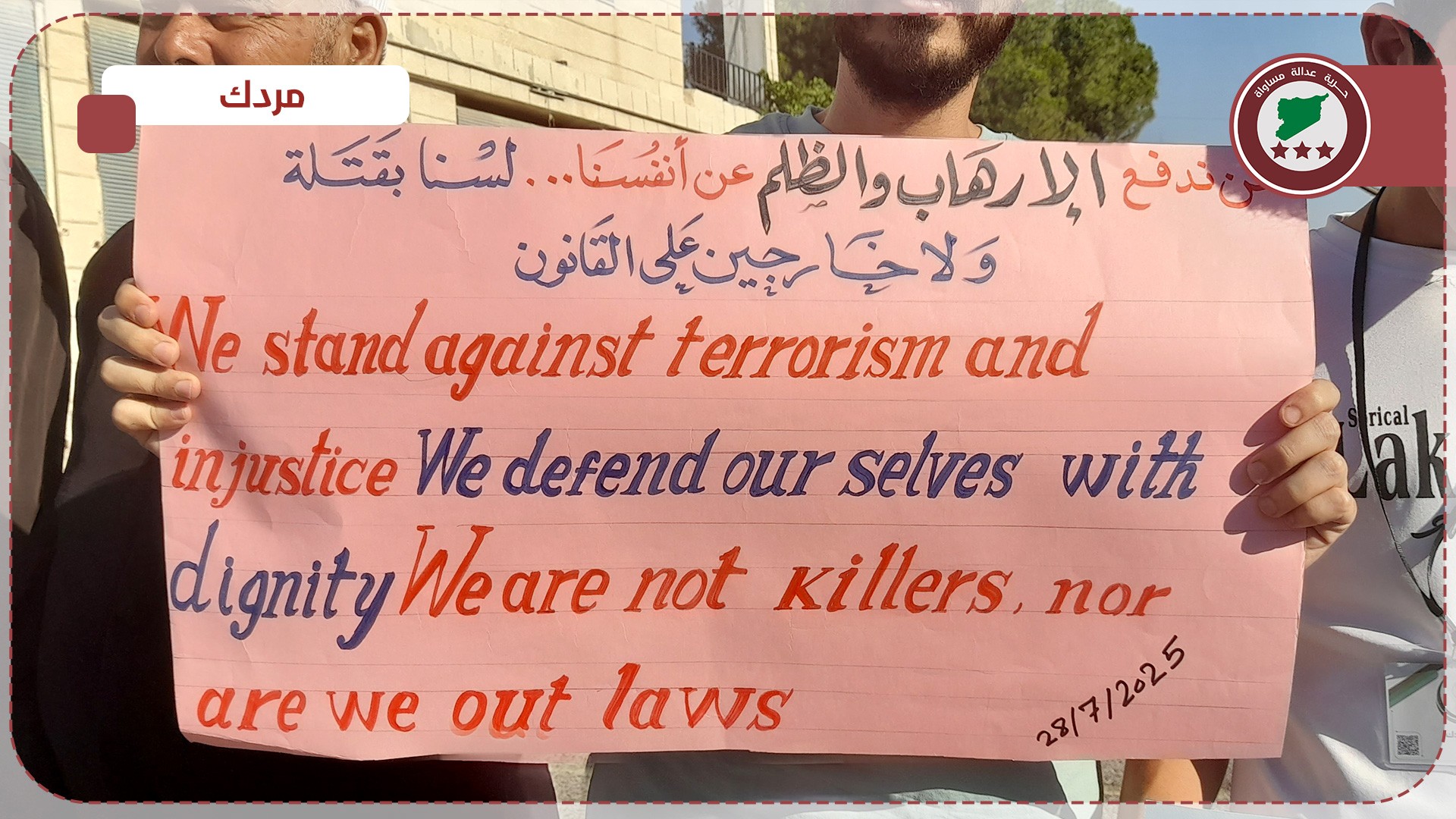

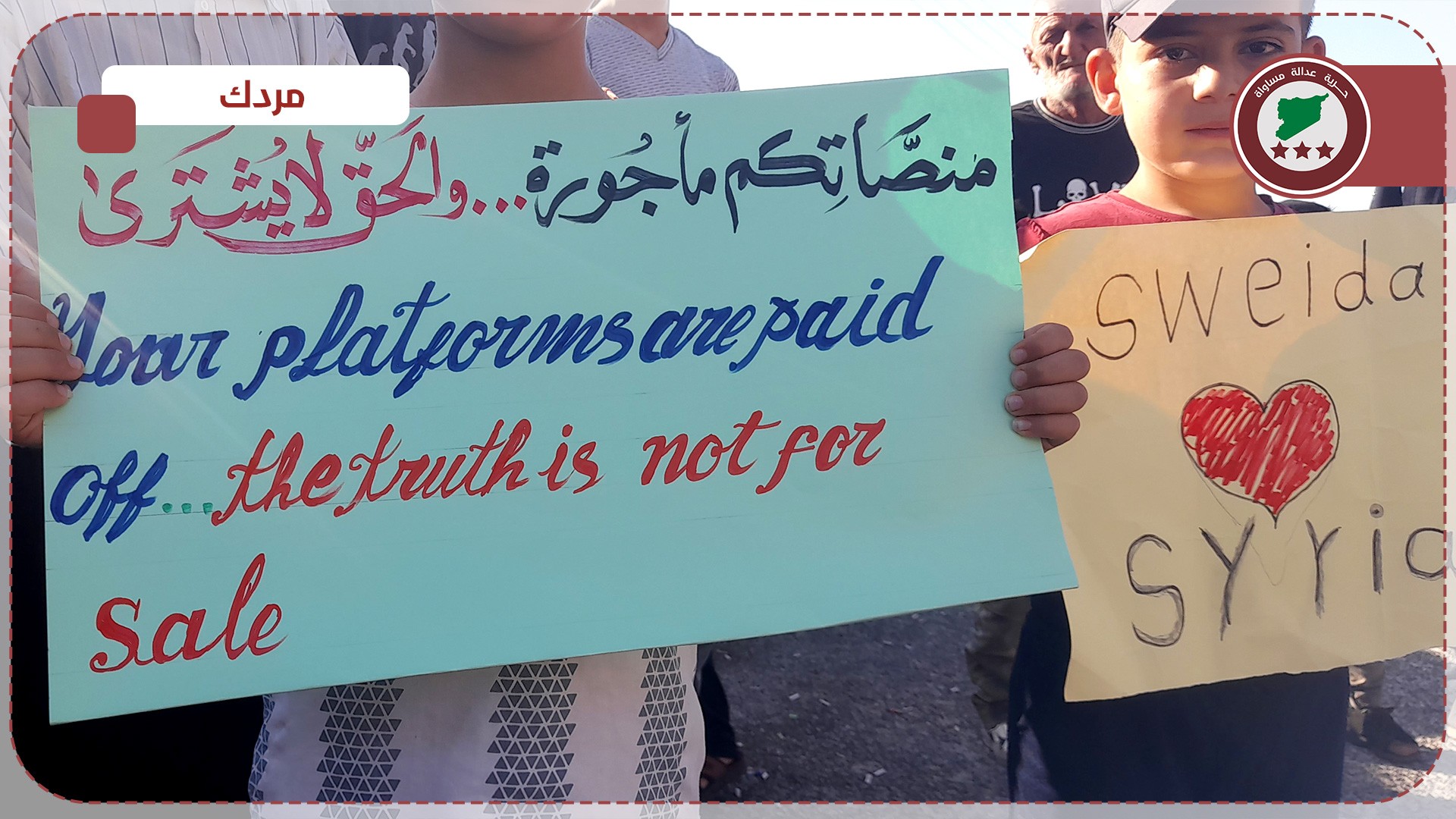

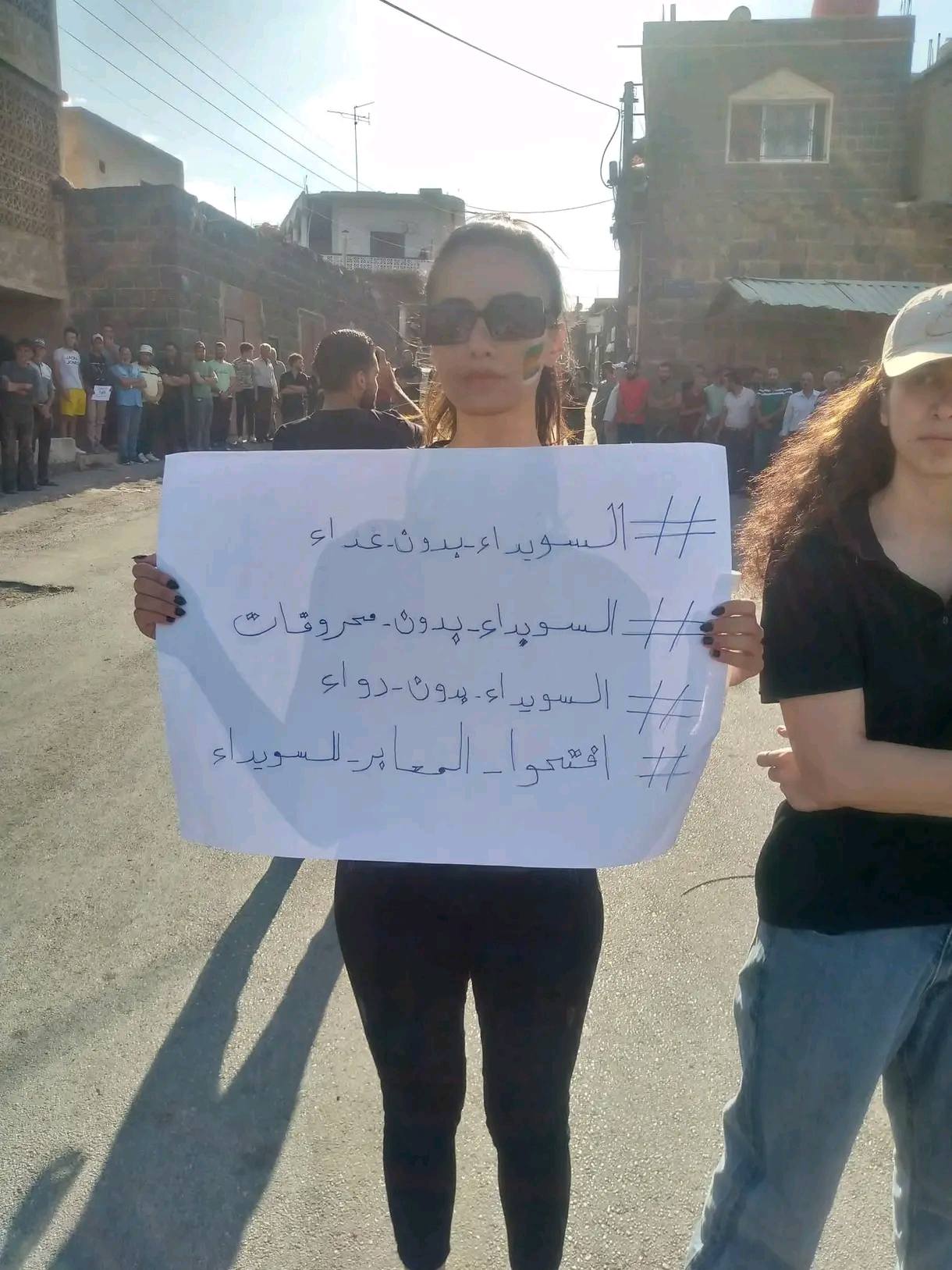

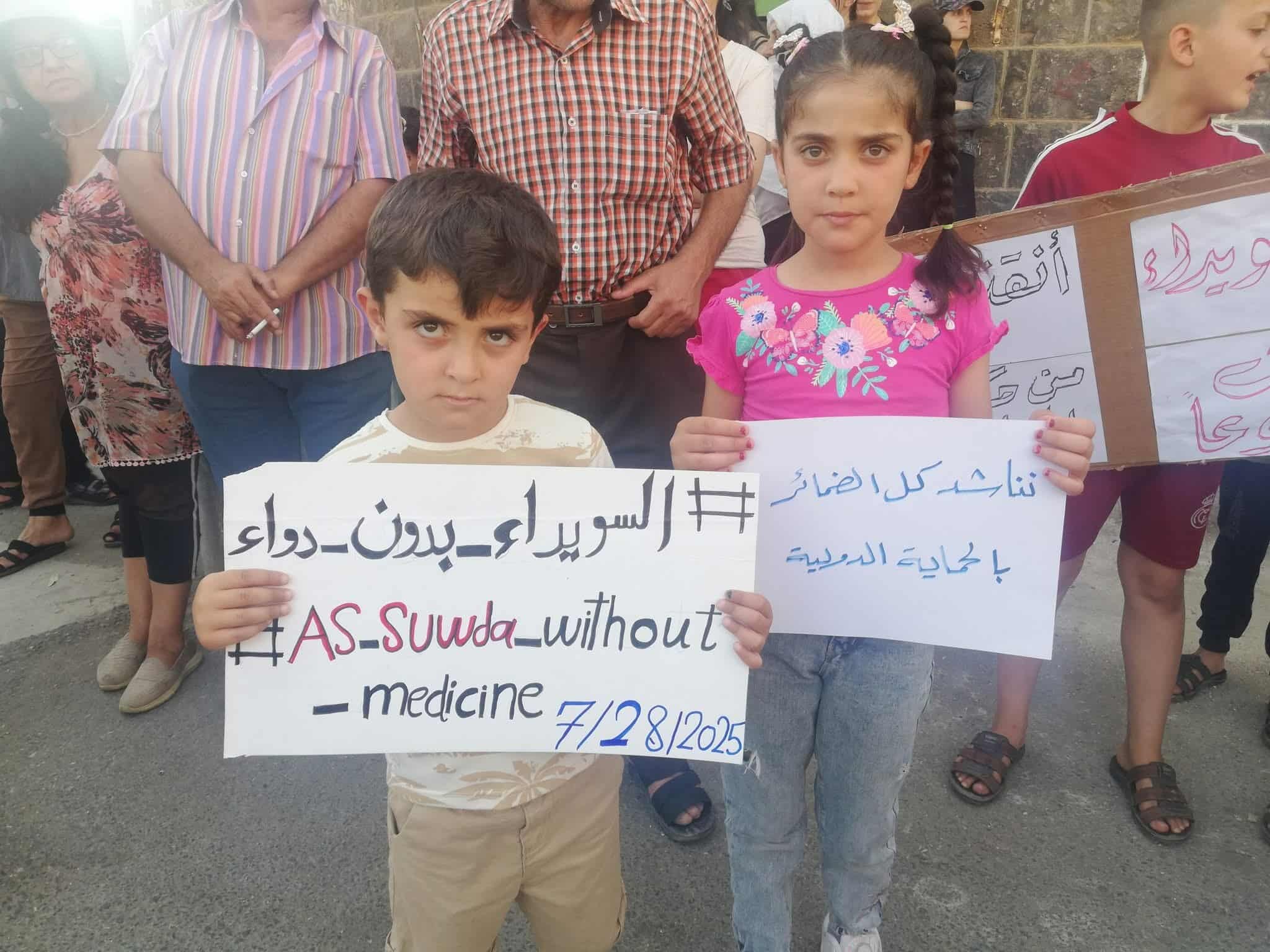

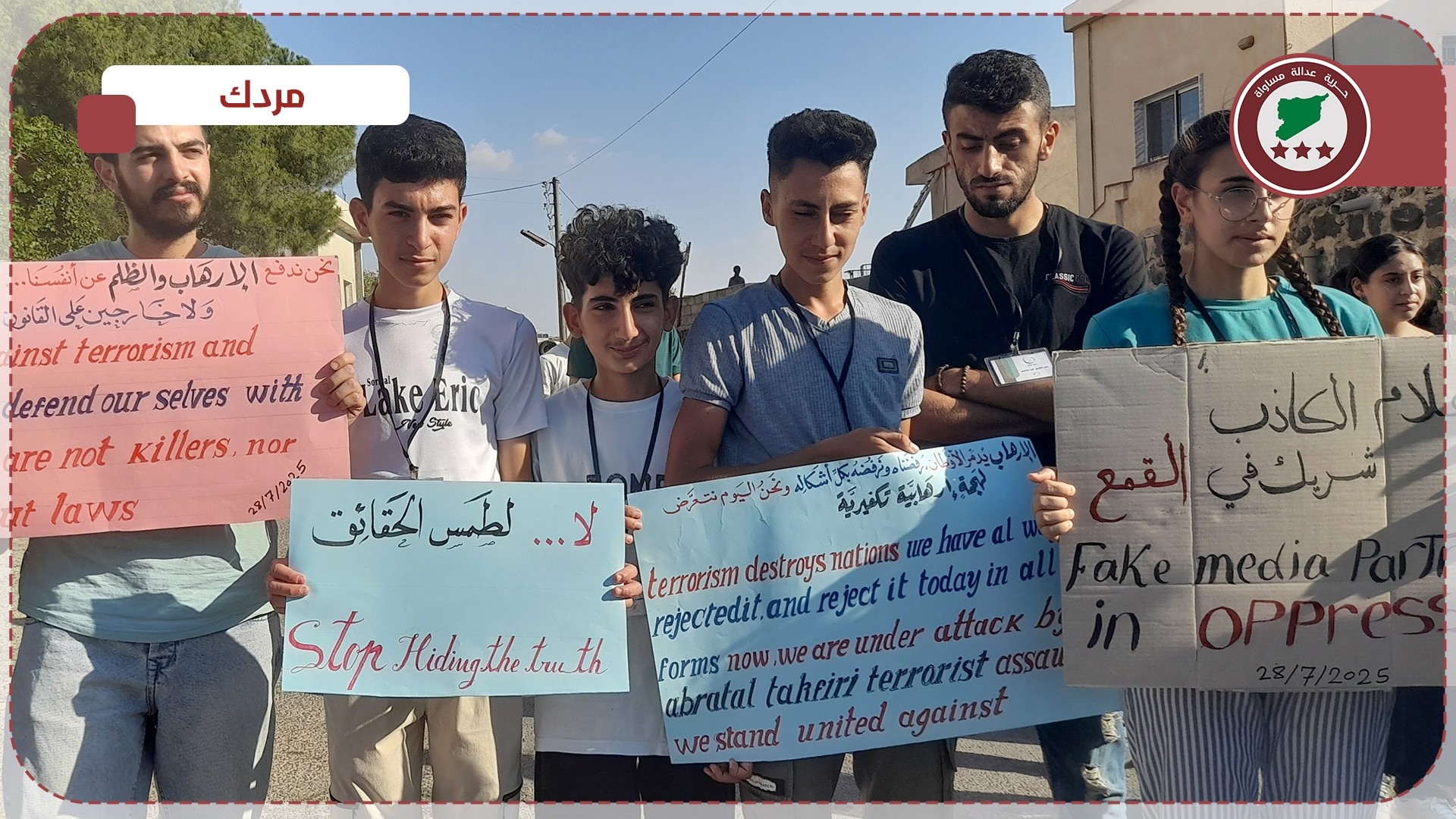

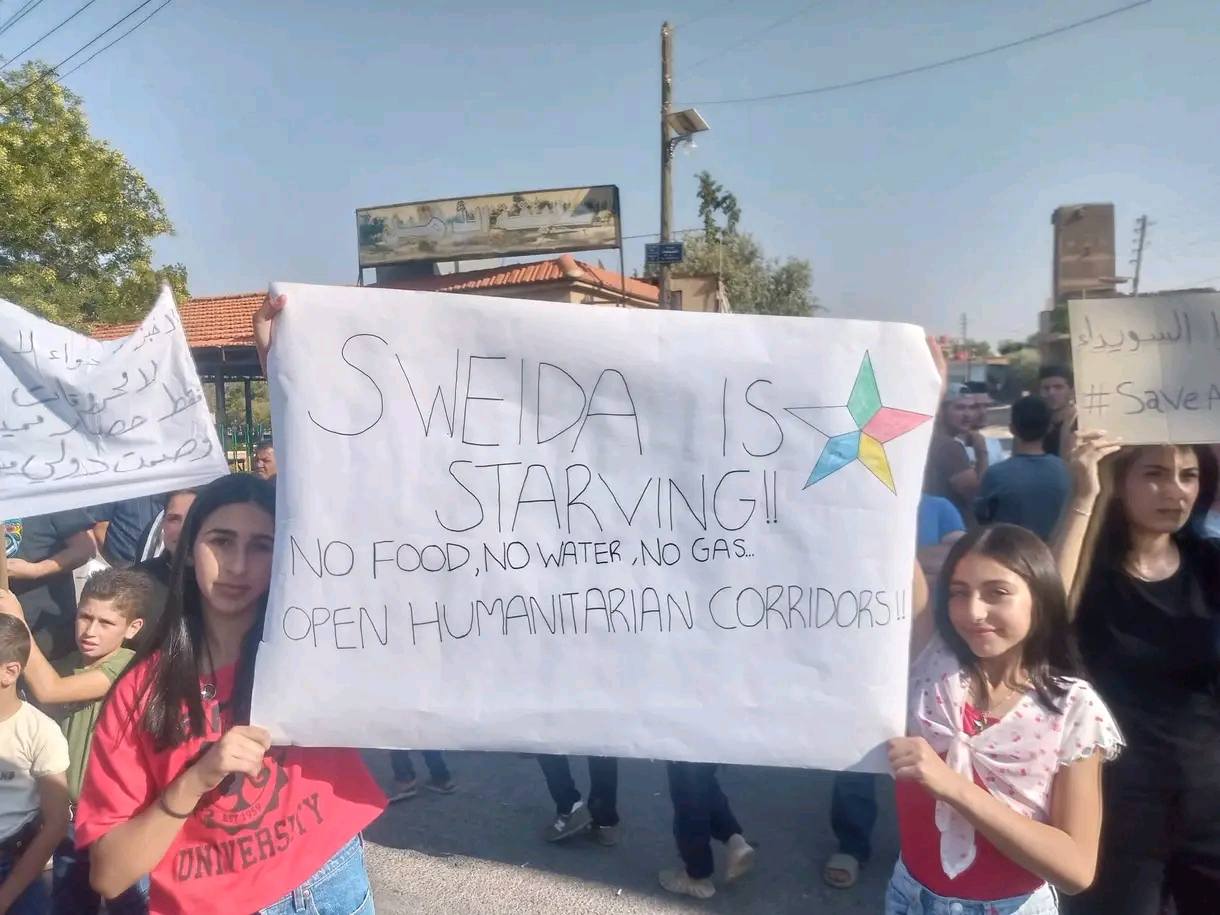

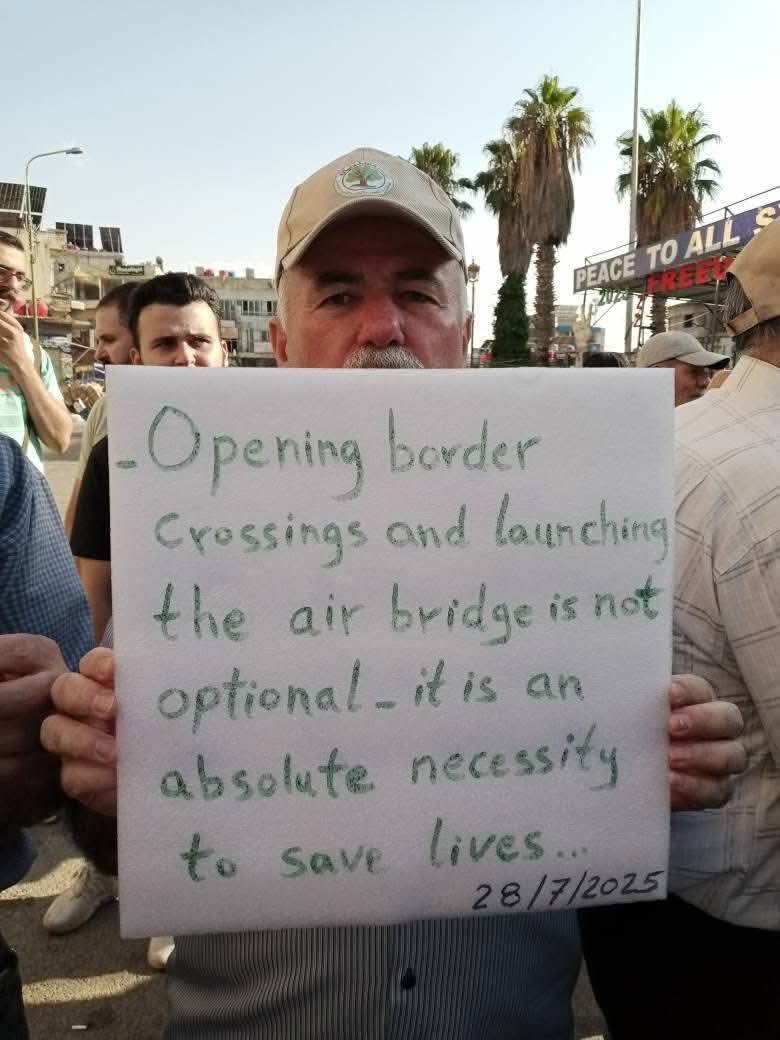

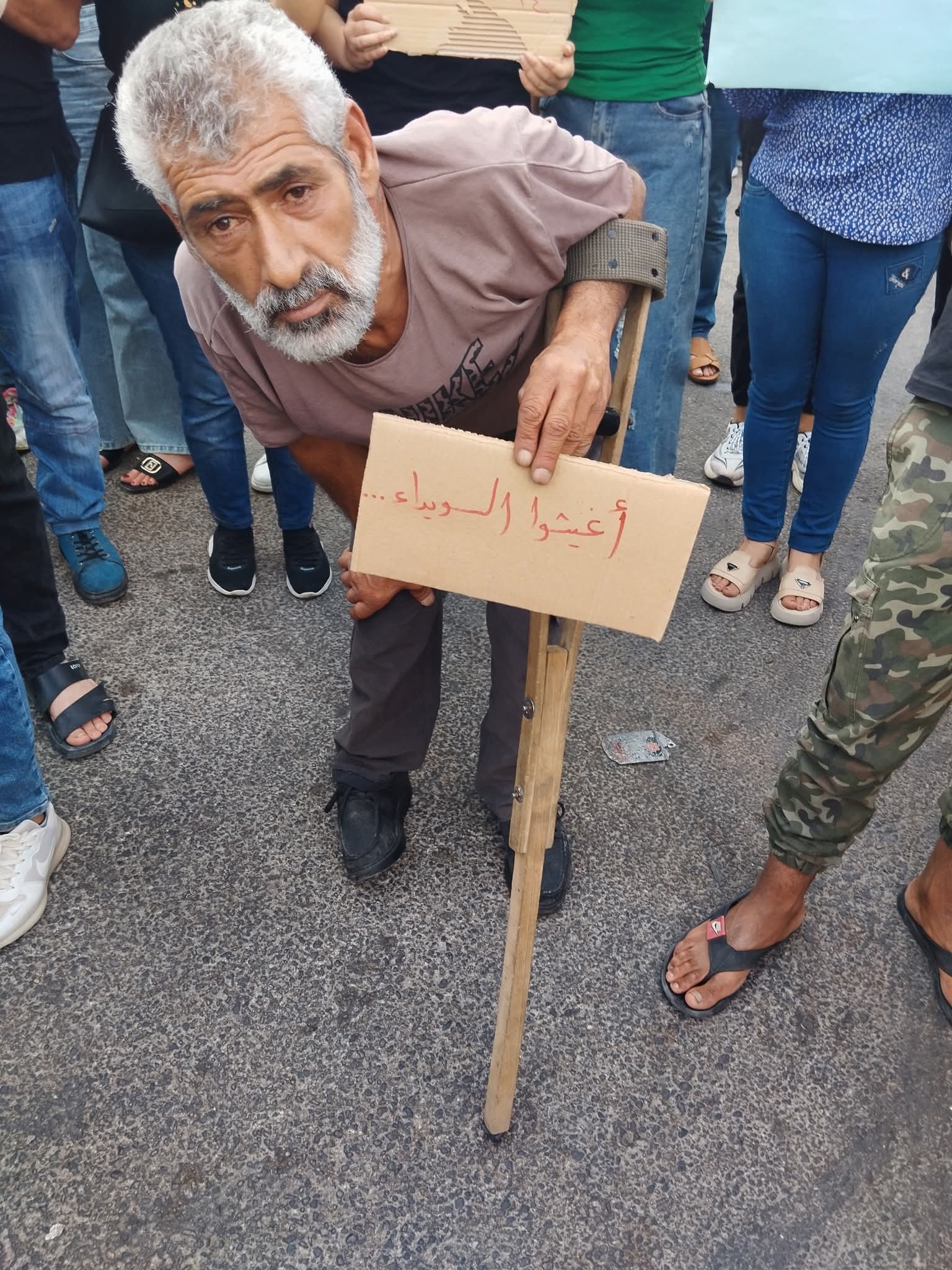

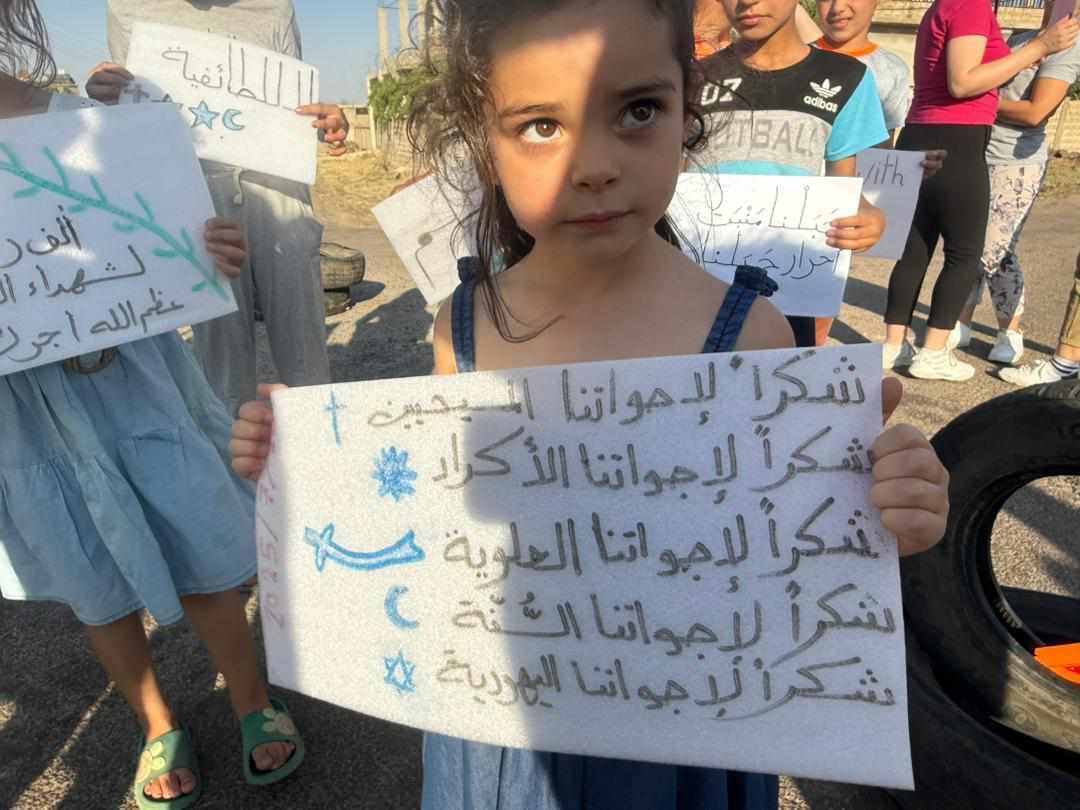

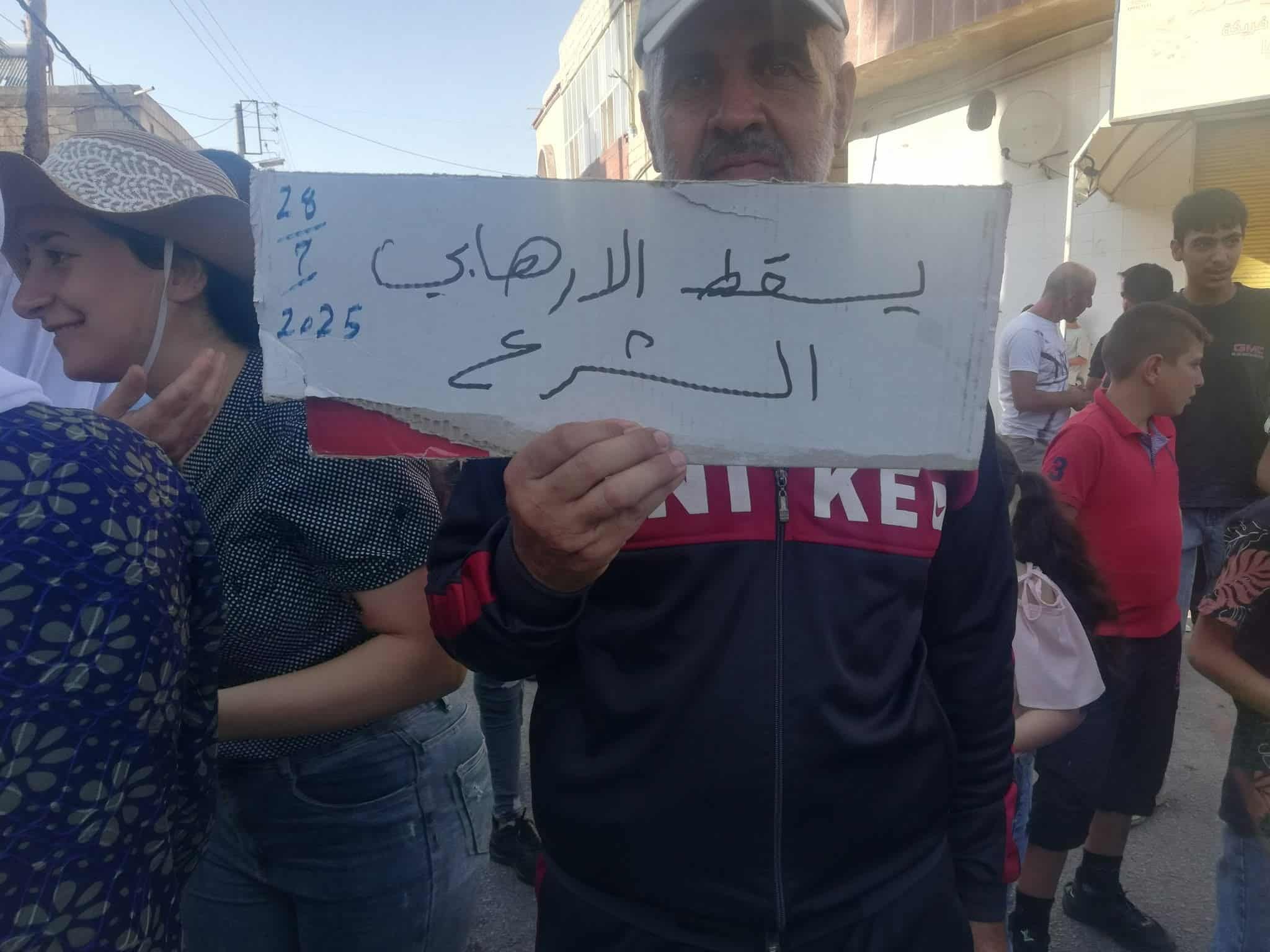

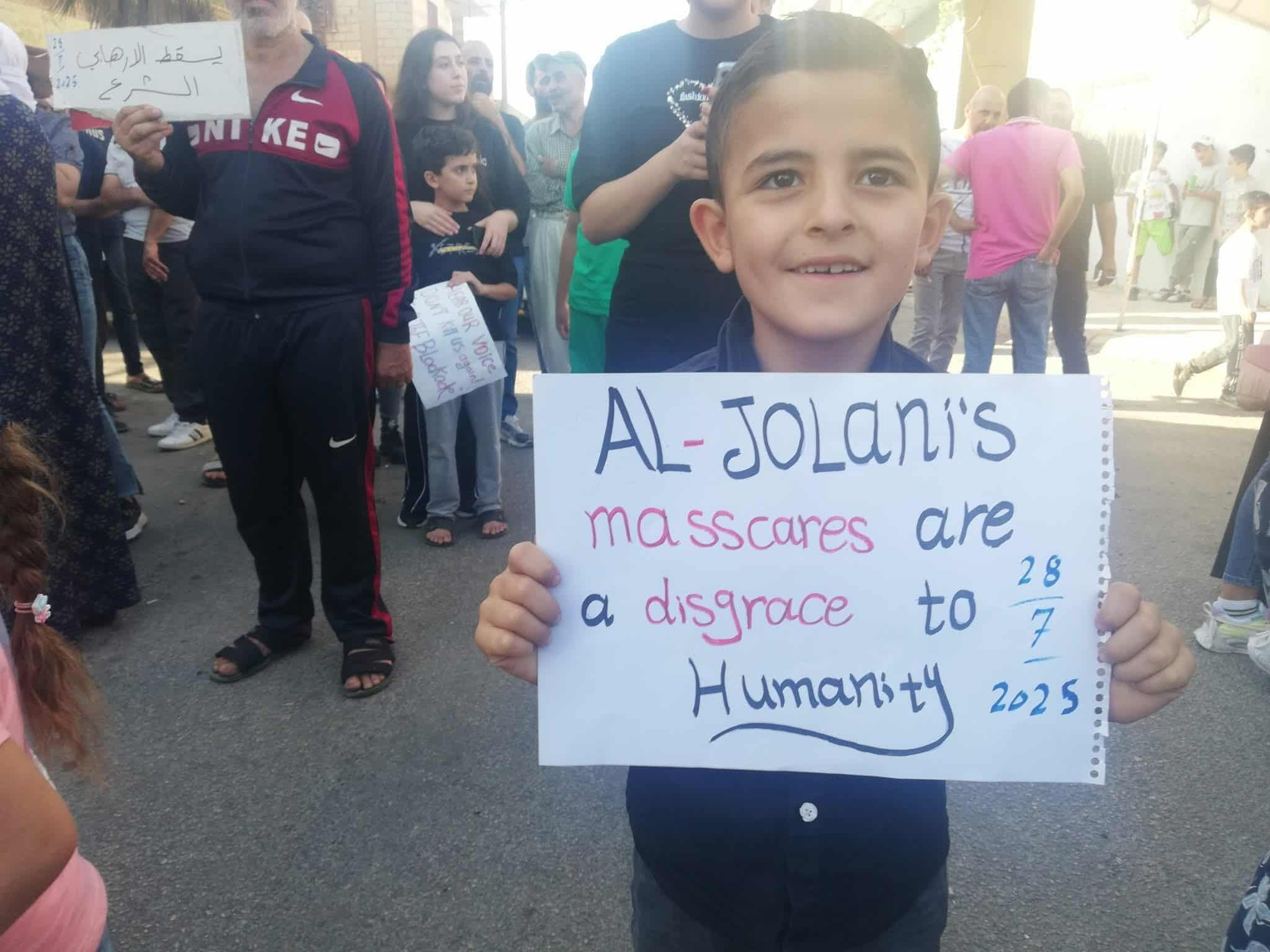

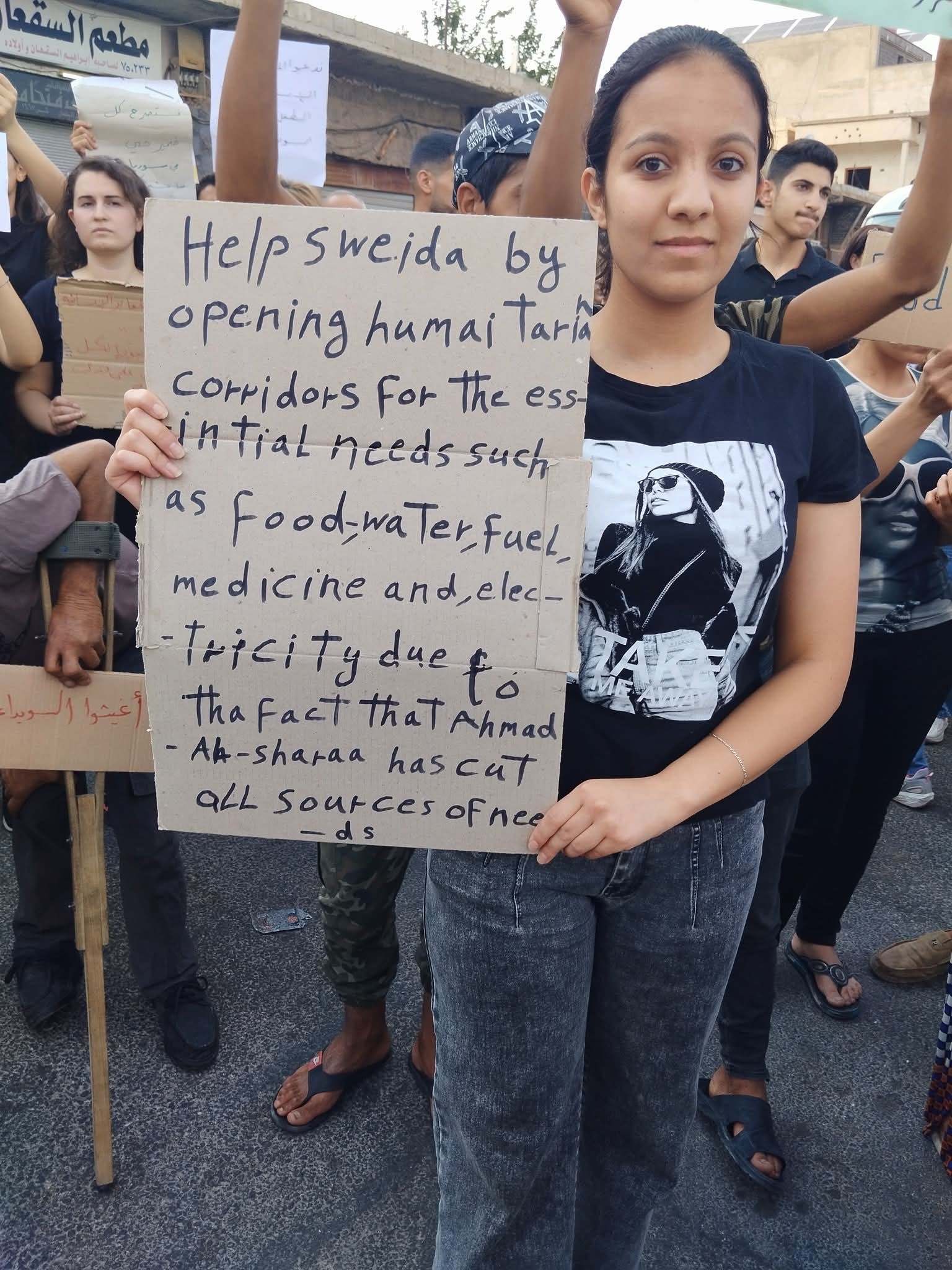

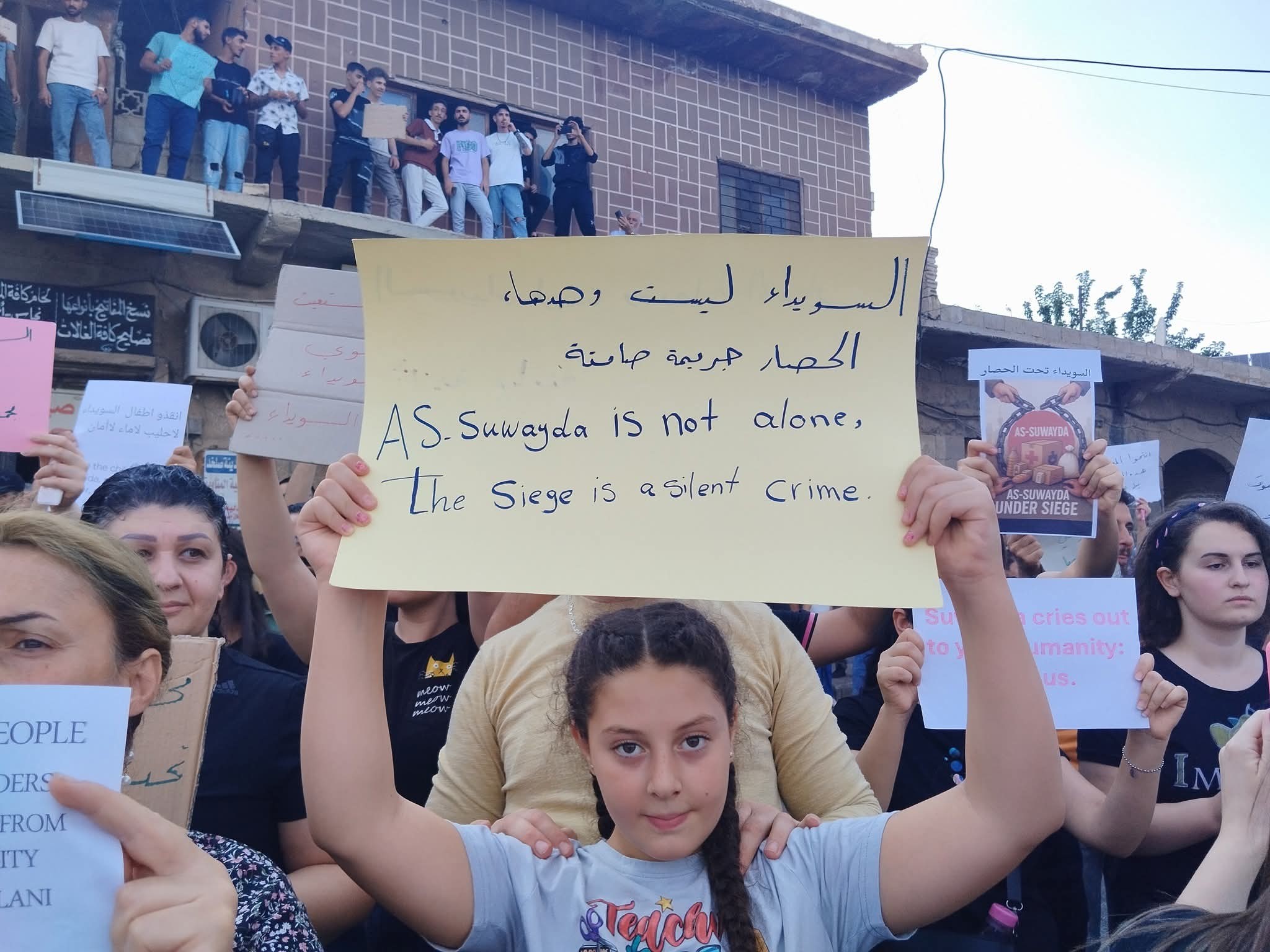

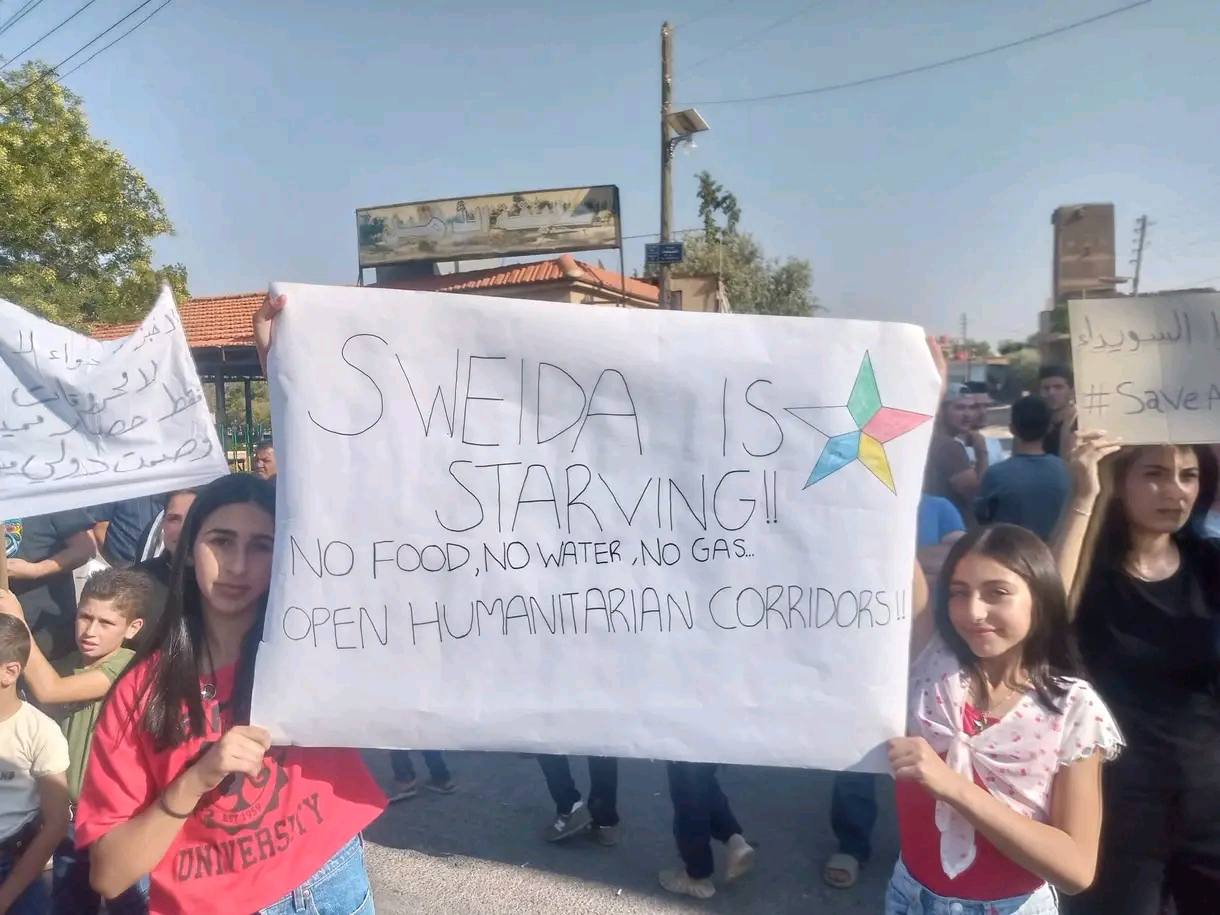

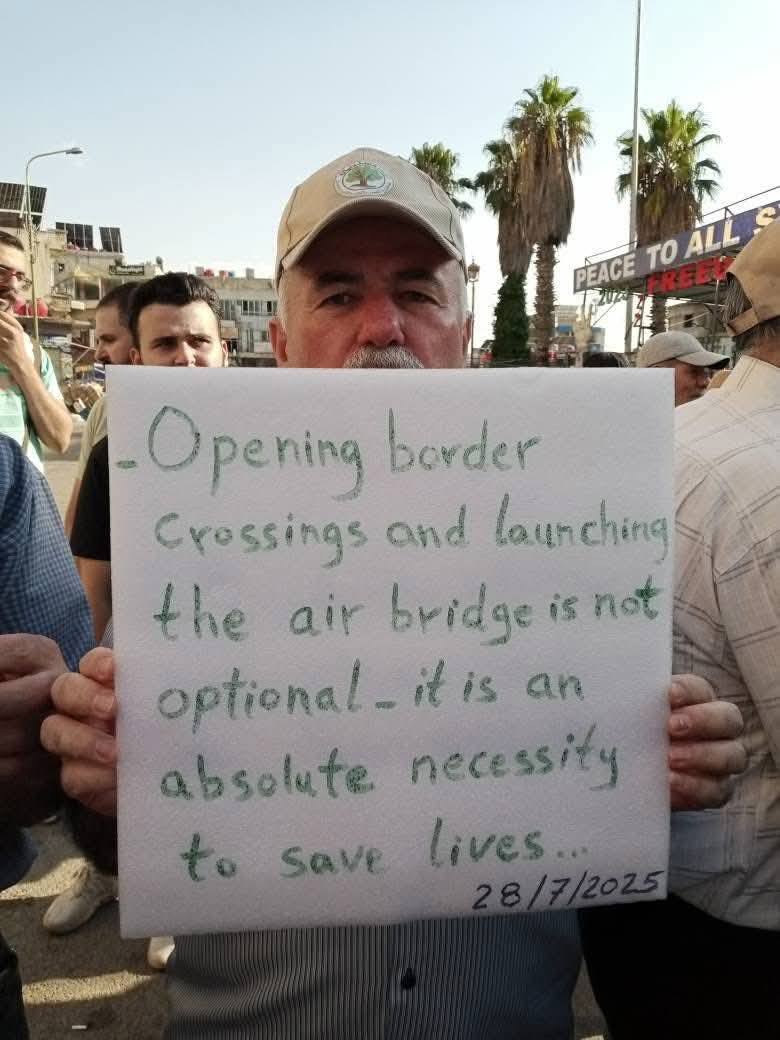

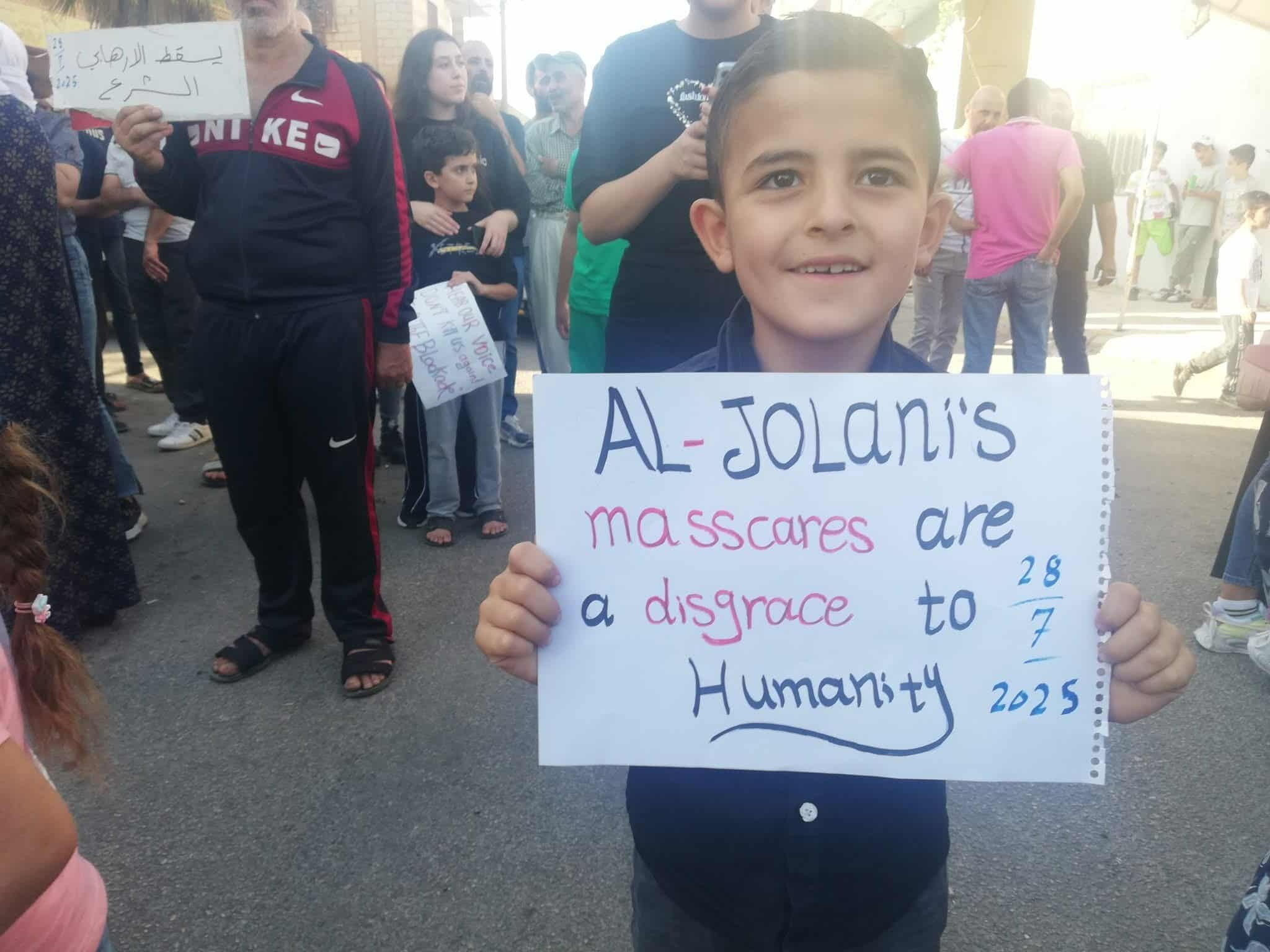

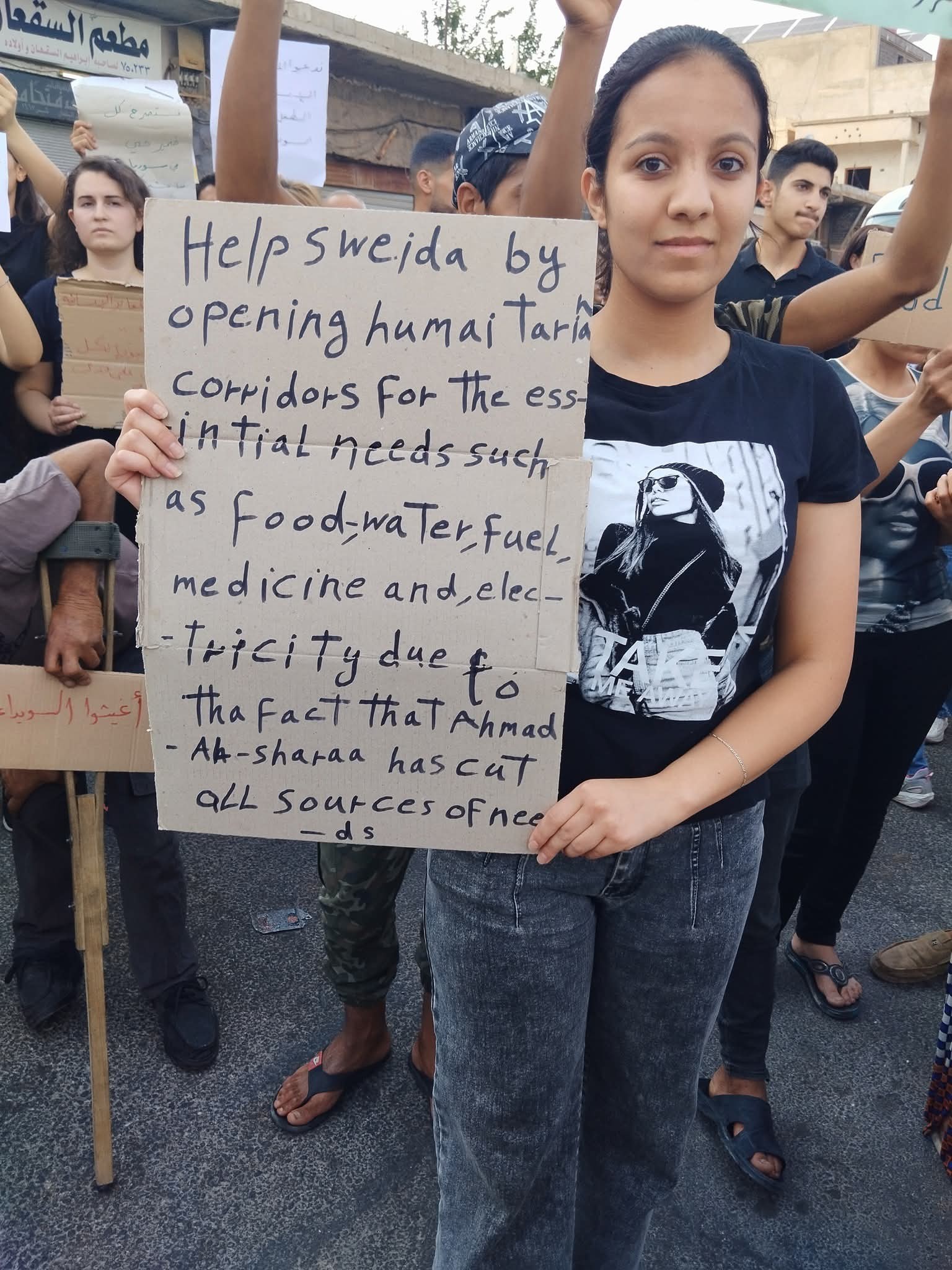

The population of Suwayda has been protesting regularly since the end of the massacres, attempting to alert international opinion to the siege they are enduring and the criminal nature of the government’s policies.

More than six months after the military assault, 34 villages remain occupied by government forces, who have made Mazraa the administrative center of the occupied area. Governor Mustafa Bakour is organizing the cosmetic rehabilitation of hundreds of burned houses in order to conceal the extent of the crimes committed, while nearly 190,000 residents remain displaced outside the area. Earth barriers cut off a number of roads and access to the occupied area remains hampered, while armed groups continue to use the villages of Mazraa, Walgha, and Al-Mansoura as a launching pad for regular raids and strikes against Druze positions, particularly the villages of Umm Zeytoun, Najran, Majdal, Remat Hazem, and the western suburbs of Suwayda city. Although the road to Damascus is officially reopened to trafic, movement is extremely limited and many men in the province are de facto housebound, as they have been for the past ten years, for fear of being associated with combatants and arrested at checkpoints.

All these factors do not bode well for the weeks and months ahead, with foreign governments seemingly agreeing to give carte blanche to the unelected president Ahmad al-Sharaa, who for many Syrians has never ceased to be the warlord Abu Mohammad al-Jolani.

Left: Map of the Suwayda province showing the attacked and occupied areas | Above: Map of Suwayda city neighborhoods.

Summary Abuses and Killings (Non-exhaustive list)

-

- On July 15 at around 9:45 a.m. in the town of Al-Thaala, located 10 km west of Suwayda city, nine civilians were executed in the courtyard of their home by men in military uniforms. Among them were two children aged 13 and 15. The victims are from Akhwan, Dahouk, and Aouj families.

- On July 15, four civilians, including a 16-year-old child, were executed in their home in the Al-Khudr neighborhood of the city of Suwayda. The victims were members of the Saleh and Mahasen families.

- On July 15, three civilians belonging to the Hamidan family, one of whom were disabled, were executed at their home in the city of Suwayda.

- On July 15, around noon, armed men forced their way into the Radwan family home and executed thirteen civilians from the same family in their guesthouse.

- On July 15, armed men entered the Arnous family’s apartment and forced three young men to jump from the balcony while shooting at them. The perpetrators filmed their actions. Prior to this, the father of the family was executed in the building. All four victims were members of the Arnous family.

- On July 15 at around 5:30 p.m. on Tishrin Square in the center of Suwayda, seven civilians, including one American citizen, were executed in the street after being abducted from their homes. The perpetrators filmed their actions. The victims were members of the Saraya family.

- On July 15, in the Nahda neighborhood of the city of Suwayda, six civilians from the Qarzab family were executed in their car as they attempted to leave the city.

- On July 15, near the Al-Khudr neighborhood of Suwayda, eight members of the Shuhayib family were executed on the side of the road leading to Al-Thaala.

- On July 16, at dawn in the National Hospital neighborhood of Suwayda twelve civilians were forcibly taken from their home to the ground floor of a building under construction located 140 meters South West from the entrance to the hospital and summarily executed on a pile of rubble and rubbish. The victims are from Dbeisi, Abu Maghdab, Shaarani, Zain, Hatem, Abu Faour, Qarqout, Abu Qaisar and Abu Fakhr families.

- On July 16 at 8:45 a.m. in the Al-Thawra neighborhood south of Suwayda city, five civilians were executed in and near their car as they attempted to leave the city. Three children were pulled from the vehicle before their relatives were executed and were kidnapped by the perpetrators. The scene was filmed by a surveillance camera. The victims were members of the Barbour, Musleh, Raef, and Ghanem families.

- On July 16 around 10:00 a.m. in the Al-Jawlan neighborhood of Suwayda, armed men broke into the Baeini – Abu Saadeh family home and executed four members of the family, including a teenager. Their bodies were found burned.

- On July 16, around 12:30 p.m. in the Al-Jaala neighborhood of Suwayda, four members of the Jarira family, including two 12-year-old children, were shot and killed in their car as they attempted to leave the city. A young girl survived by hiding in a ditch until dawn the next day.

- On the morning of July 16, in the old town of Suwayda, a group of men in military uniforms entered the Badr family home, where more than forty people had taken refuge, after throwing grenades inside. Twenty-three civilians were executed, some after being beaten and stabbed with knives. The victims are from Badr, Los, Kamal, Taqi, Shtay and Melhem families.

- On the morning of July 16, in the Al-Koum neighborhood of Suwayda (on the southern outskirts of the city), armed men broke into the Mezher family home and executed fourteen civilians. The victims are from Mezher, Halabi, Hamoud and Khatib families.

- On July 16, at the intersection of the main avenue (Route 110) and Al-Jandi al-Majhul Street, seven civilians were executed in the street after being abducted from their homes. The victims are from Mazhar, Ahmad, Ashqar, Hassoun and Abu Hamza families.

- During the day of July 16, a number of civilians were killed by sniper fire as they attempted to leave the city or seek shelter. Among them are several children. Non-exhaustive list of victims: Tala Al-Shufi (14 years old), Amer Hilal and her daughter Ghena (14), Qais Al-Nabwani (13), Dr Taalat Amer, Salama Al-Jaber…

- On July 17, in the village of Sahwet Blata, located 6 km southeast of the city of Suwayda, eleven members of the Gharz Ad-Din family were executed in their home. Among the victims was a three-month-old baby whose body was found in a cardboard box.

- On July 18, in the village of Walgha, located 4 km northwest of the city of Suwayda, five members of the Kfeiri family were executed in their home.

- On July 19, in the Mazraa neighborhood (Dawar Thaali) located northwest of the city of Suwayda, three members of the Sayyid family, including an 80-year-old disabled man, his wife, and their daughter, were executed and their bodies burned.