The Druze of Lebanon and Syria, a long history of insubordination

About the author: Cédric Domenjoud is an independent researcher and activist based in Europe. His research areas focus on exile, political violence, colonialism, and community self-defense, particularly in Western Europe, the former USSR, and the Levant. He is investigating the survival and self-defense of Syrian communities and developing a documentary film about Suwayda, as part of the Fajawat Initiative.

With the Assad regime having just fallen and the issue of disarming the Druze and Kurdish communities making headlines, it is worth recalling the highly political history of the Druze community in Syria and Lebanon. Here are a few key points.

The Druze are a religious community attached to a heterodox creed of Ismaili Shi’ite Islam, which originated in Egypt under the leadership of Imam Hamza ibn Ali ibn Ahmad in the early 11th century. The Druze faith takes its name from the preacher Muhammad ad-Darazi, although some of his followers do not recognize Ad-Darazi and he was disowned by Hamza ibn Ali before being executed on the orders of the caliph Al-Hakim bi-amr Allah. The Druze prefer to define themselves as “Muwahideen” (Unitarians) or “Banu Ma’ruf” (Children of Maarouf), although the origin of this term remains uncertain.

The Druze religion, like Sufism, takes a philosophical and syncretic approach to faith, recognizing neither the rigid precepts nor the prophets of Islam. Although this belief spread to Cairo under the Fatimid caliphate of al-Hakim, who was deified by the Druze, it was soon persecuted by the rest of the Muslim community after al-Hakim’s death in 1021, and so the Druze were exiled to Bilad el-Cham (present-day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine), particularly to Mount Lebanon and the Hauran. But it was around the beginning of the 19th century that the Druze community in Hauran gained strength, after a large part of the community had been expelled from Mount Lebanon by the Ottoman authorities. The Hauran mountain was then named jebel al-Druze.

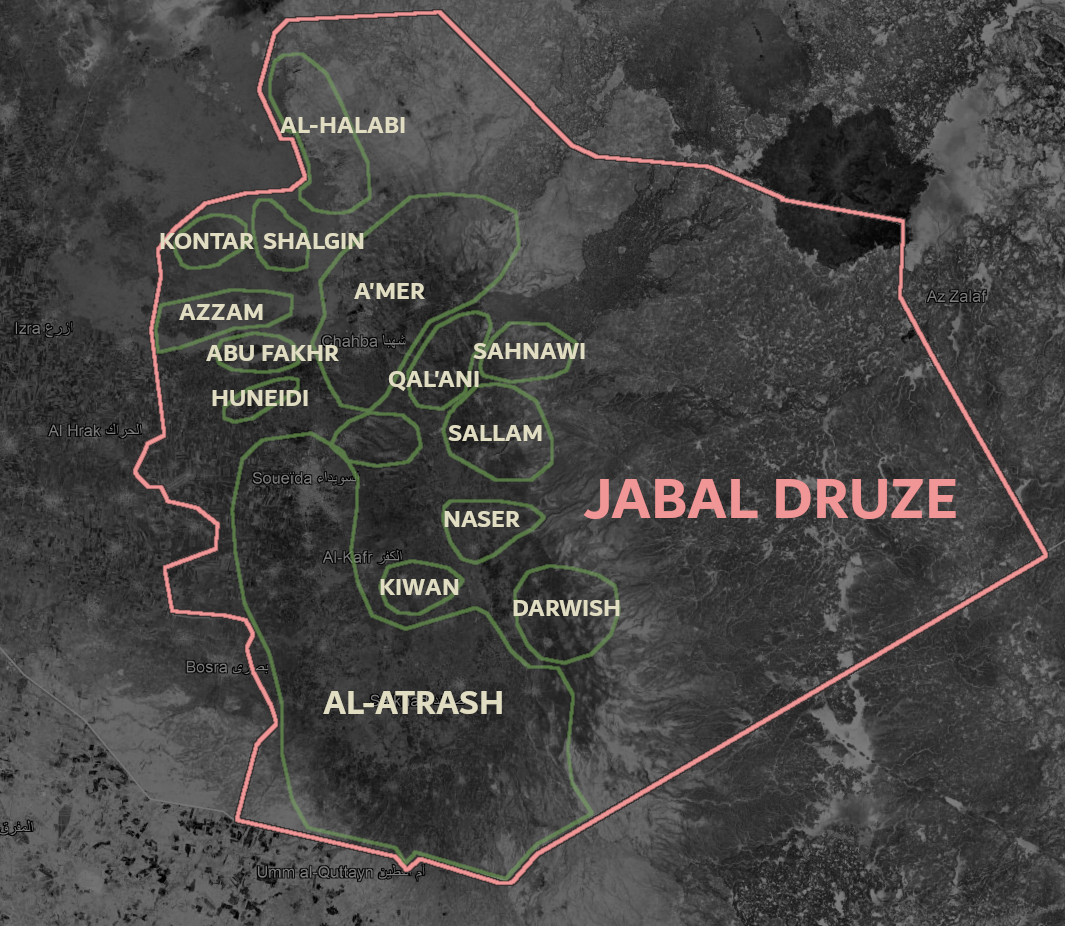

The main Druze families and clans in the 19th century

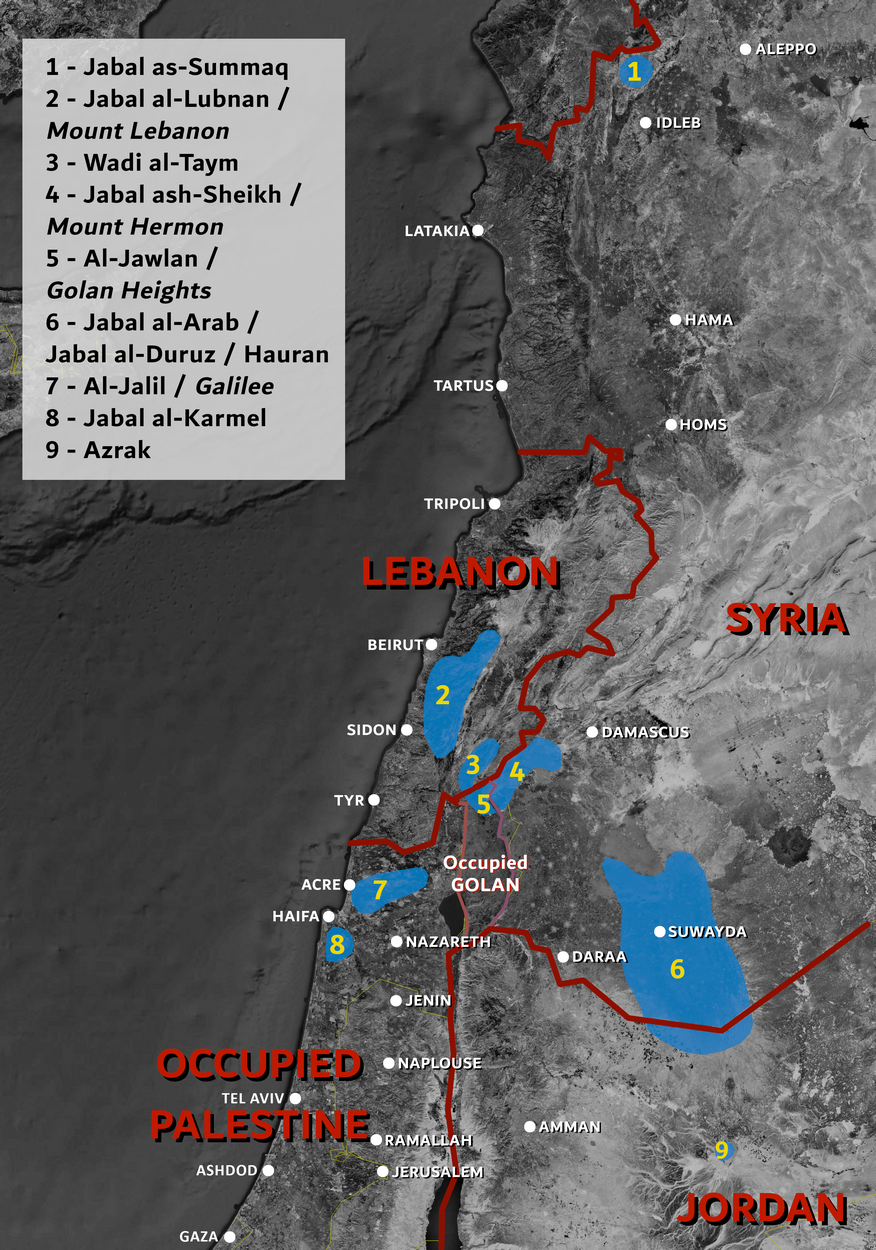

Today, Suwayda governorate is home to the majority of the world’s Druze community, some 700,000 people. The Lebanese Druze are the second largest community, numbering 250,000. In Syria, several Druze settlements also exist in Jebel al-Summaq (Idlib, 25,000 people), Jebel al-Sheikh and al-Juwlan (Quneitra, 30,000 people) and Jaramana (Damascus suburbs, 50,000 people). Finally, outside Syria and Lebanon, the largest Druze communities are to be found in occupied Palestine (Galilee and Mount Karmel, 130,000), Venezuela (100,000), Jordan (20,000), North America (30,000), Colombia (3,000) and Australia (3,000).

The Druze community is structured along traditional clan lines, with large families exerting a dominant influence. Until the mid-18th century, Hauran (or Jabal Druze) was dominated by the Hamdan family, whose hegemony was challenged in the 1850s by Al-Atrash family. The conflict between the two families and their respective allies between 1856 and 1870 was finally settled by the intervention of the Ottoman authorities, who divided the region into four sub-districts, the largest of which was that of Al-Atrash family, comprising 18 villages out of the 62 in Hauran at the time.

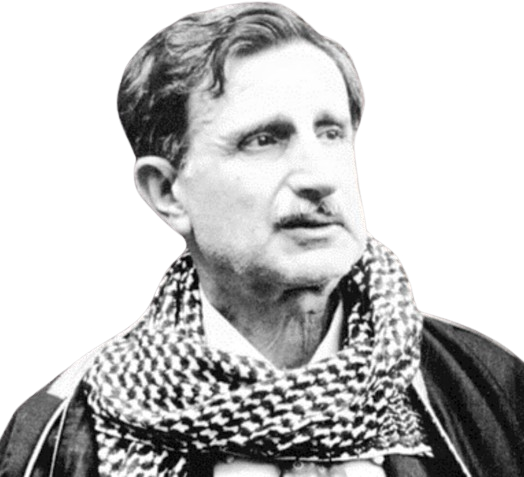

Zuqan al-Atrash

Rebellion against Turkish-Ottoman authority…

In 1878, the semi-autonomy acquired by the Hauran was called into question by Ottoman military intervention, which sought to put an end to the conflicts between the Druze and their neighbors in the plain (now Daraa). The Ottoman authorities imposed a new form of governance under the leadership of Ibrahim al-Atrash, and the payment of taxes to the Druze community, particularly to peasants. Between 1887 and 1910, a series of conflicts ensued, first between the region’s peasants and Al-Atrash family, then between Ibrahim’s brothers – Shibli and Yahia – and the Ottoman authorities. In 1909, the revolt against the Ottomans led by their nephew Zuqan al-Atrash failed at the battle of Al-Kefr, and he was executed the following year. His son Sultan took over at the time of the great Arab revolt of 1918…

During the 1914-1918 war, Ottoman rule left Jabal Druze relatively undisturbed. Sultan al-Atrash forged links with the pan-Arab movements involved in the great Arab revolt of the Hijaz (Saudi Arabia) and raised the Arab flag on the fortress of Salkhad, south of the Suwayda region, and on his house in Al-Qurayya. He sent a reinforcement of 1,000 fighters to Aqaba in 1917, then joined the revolt himself with 300 fighters at Bosra, before seizing Damascus on September 29, 1918. Sultan became a general in Emir Faisal’s army and Syria gained independence. This was short-lived, however, as Syria was occupied by the French in July 1920. Jabal Druze became one of the five states of the new French colony.

Sultan al-Atrash

Sultan al-Atrash

…then against French colonialism

Sultan al-Atrash first clashed with the French in 1922, when his host, Lebanese Shi’ite rebel leader Adham Khanjar, was arrested at his home in his absence. Sultan demanded his release, then attacked a French convoy believed to be carrying the prisoner. In retaliation for the attack, the French demolished his house and ordered his arrest, but Sultan took refuge in Jordan, from where he led raids against the French forces. Temporarily pardoned and allowed to return home, he led the Syrian revolt of 1925-1927, declaring revolution against the French occupiers. Initially victorious, the Great Syrian Revolt was finally defeated by the French army and Sultan was sentenced to death. He took refuge in Transjordan, before being pardoned again and invited to sign the Syrian Independence Treaty in 1937. He received a hero’s welcome in Syria, a reputation he retains to this day. When the treaty failed to secure Syria’s independence in May 1945, the Syrians once again revolted against the French occupiers, who sent in the army and killed around a thousand Syrians. In Hauran, the French army was defeated by the Druze under the command of Sultan al-Atrash, before the British intervention that put a definitive end to the French mandate on April 17, 1946.

Editor’s note: the commitment of the Al-Atrash family must be seen in the context of Arab conservatism and nationalism, which did not challenge traditional clan, patriarchal and authoritarian structures. However, their constant opposition since the 19th century to foreign imperialism and the abusive authority of central powers made them precursors in the anti-colonial struggles of the second third of the 20th century. Their struggle can also be seen as carrying within it the seeds of community struggles for autonomy and self-defence, which will be discussed in Suwayda in the recent period (years 2010-2020). Sultan al-Atrash is also known for his stance in favor of multiculturalism and secularism.

الدين لله، والوطن للجميع

Religion is for God, Homeland is for everyone

Resistance to Israeli colonialism

When the British transferred their domination of Palestine to Zionist settlers in Europe and America, and the latter began ethnically cleansing the Palestinians from December 18, 1947, Sultan al-Atrash called for the formation of the Arab Liberation Army of Palestine. Under the command of future Syrian president Adib Shishakli, this army entered Palestine from Syria on January 8, 1948, as part of the First Arab-Israeli War.

Kamal Jumblatt

Only a year apart, on May 1, 1949, Druze intellectual and political leader Kamal Jumblatt founded the Progressive Socialist Party, then he called for the first convention of Arab Socialist Parties in May 1951 and began to establish links with the Palestinian Left Resistance, embodied by the Fedayeen movement. Jumblatt then turned the PSP into an armed movement integrated into the Lebanese National Movement, a coalition of 12 left-wing parties and movements founded in 1969 to support the Palestine Liberation Organization, itself created five years earlier and then led by Yasser Arafat. Jumblatt is the leader of the Lebanese National Movement (LNM).

The entire period between 1952 and 1975 was characterized by growing sectarian tensions between secular left-wing movements – anti-imperialist and pro-Palestinian – and the pro-Western Christian Maronite elites, who dominated the Lebanese political landscape at the time. From 1970 onwards, these tensions were heightened by the significant increase in the number of Palestinian fighters in Lebanon, following their expulsion from Jordan, and leading to a considerable increase in the influence of Palestinian movements in the country. These tensions culminated in the massacres of Palestinian civilians by Christian Phalangists (Kataeb) at Ain el-Rummaneh on April 13, 1975 (30 dead) and at Karantina (between 1,000 and 1,500 dead), followed by the massacre of Christian civilians at Damour (150 to 580 dead) in January 1976.

Syrian President Hafez al-Assad – whose Ba’ath party had until then supported the Palestinian left and its allies – took up the cause of the Christian Falangists and proposed an agreement involving the reduction of Palestinian influence in Lebanon. The PLO refused, and in March 1976, Kamal Jumblatt went to Damascus to express his disagreement to Hafez al-Assad. The following month, the LNM and the PLO took control of 80% of Lebanon, but in June the Syrian army intervened in Lebanon. During the summer, the Christian militias who had been besieging the Palestinian camp of Tell al-Zaatar since the beginning of the year, massacred between 2,000 and 3,000 civilians with Syrian military support. At the end of a six-month confrontation with the PLO and the LNM, a temporary ceasefire was signed, establishing the long-term occupation of Lebanon by the Syrian army and leading to the gradual – then definitive ten years later (1987) – annihilation of the Palestinian Resistance in Lebanon.

On March 16, 1977, Kamal Jumblatt was assassinated by gunmen hired by Hafez al-Assad’s brother, Rifaat. Many left-wing personalities attended his funeral, and Yasser Arafat delivered a powerful eulogy for his ally and friend.

Excerpt from the film “Greetings to Kamal Jumblatt”, Maroun Bagdadi, 1977, 57 mm

Editor’s note: We are not here to idealize Kamal Jumblatt’s character, and we believe that leaders should never be heroes. However, we do not believe that Kamal Jumblatt is guilty of any crimes, nor that he has propagated feelings of hatred based on the ethnic or religious affiliation of his opponents, contrary to what has been conveyed by certain media affiliated to the Lebanese right. Nevertheless, it must be recognized that any armed movement has at one time or another been associated with or directly involved in the commission of crimes or acts of vengeance. This was notably the case with the Palestinian armed factions, and therefore their allies, as in Damour in January 1976. It’s also important to admit when a leader betrays the interests of his community, as in the case of Kamal Jumblatt’s son, Walid Jumblatt. His political choices following his father’s death and up to the present day are relatively dubious, and he does not seem to us to be worthy of his father’s political legacy.

Armed resistance to authoritarian centralism in Damascus

When the 2011 revolt against Bashar al-Assad broke out, Syria’s Druze joined the rest of the Syrian population in demonstrating in the streets of Suwayda and Jaramana, the Druze community district of Damascus.

And when the armed struggle took over from the peaceful demonstrations, Druze officer Khaldun Zein Ad-Din defected from the regime’s army on October 31, 2011. He publically declared his allegiance to the Free Syrian Army and created the “Sultan Basha al-Atrash” batallion, made up of 120 Druze fighters.

Khaldun Zein Ad-Din

Fadlallah Zein Ad-Din

Amira Abu Bahsas

He was joined by his brother Fadlallah Zein Ad-Din in July 2012. Denounced by informers, they are besieged and Khaldun is killed with 16 other of their companions in Tall al-Maseeh on January 13, 2013. His brother announced his death in a statement ten days later. The Progressive Socialist Party of Lebanon organized a ceremony in their honor, and he became the symbol of the revolutionary and opposition movement in Suwayda. On March 21, 2013, his wife Amira Abu Bahsas publicly declared that she too would join her late husband’s battalion, becoming the first woman from Suwayda to join the Free Syrian Army.

During anti-regime demonstrations in Suwayda between 2023 and 2025, Khaldun Zein Ad-Din’s portrait is displayed in Dignity Square, where his parents Sami and Siham actively participated in the protests.

Another form of resistance to Assad’s dictatorship emerged in 2013 in Suwayda, following the forced recruitment of several dozen young men from the region. An influential sheikh in the community, Waheed al-Balous, refused to accept the community’s participation in the war against other Syrians and opposed forced recruitment. He founded the Men of Dignity Movement (“Rijal al-Karami”), which gained in popularity over the years and prevented the conscription of between 30,000 and 50,000 young men from Suwayda.

دم السوري على السوري حرام

A Syrian must not shed the blood of another Syrian

In 2015, Balous openly denounced the dictatorship, leading to his assassination in a double bomb attack on September 4, 2015. On the evening of his death, riots broke out in the region and the statue of Hafez al-Assad that had stood in Dignity Square was removed. It was never replaced. His brother Raafat, wounded in the attack, temporarily replaced him before giving up his position. Waheed al-Balous’s sons, Laith and Fahd, created a splinter group from Rijal al-Karami, the Sheikhs of Dignity (Sheikh al-Karami), which they intended to be politically more radical than their father’s movement. Despite frequent disagreements, the two movements continued to carry out joint actions, even as Rijal al-Karami drew closer to another major faction, the Forces of the Mountain (Quwwat al-Jabal). In December 2024, they joined the Southern Room for Military Operations, which also included other Druze factions and took part in the liberation of Damascus.

Waheed al-Balous

Raafat al-Balous

Laith al-Balous

Fahd al-Balous

Editor’s note: While here too we must refrain from idealizing one faction or another, we nevertheless consider that Rijal al-Karami and associated groups have, in recent years, embodied the Druze community’s imperative for self-defense and self-determination. Whether in the face of attempts by the regime’s army to impose itself by force or coercion, in the face of Islamist aggression or in the face of the predation of the gangs that have proliferated in the region, these factions have succeeded in protecting the civilian population and the general interest without committing exactions or abuses of power. Their leaders have generally answered the call of threatened communities and taken a clear stand against any outside force threatening community security. They also acted as protectors of popular demonstrations and revolts, before spontaneously joining the offensive against the regime in December 2024.

Suwayda at the heart of the revolutionary path from 2011 to 2025

Beyond the few emblematic examples of armed resistance to the authoritarian centralism of Damascus, civil society in Suwayda has never ceased to take a critical or hostile stance towards central power and the Assad dictatorship. Contrary to unfounded rumors that regularly portray the Druze as loyal to the regime, numerous examples demonstrate that the community has always succeeded in reconciling its tradition of resistance with a refusal to take sides in a conflict that very early on became confessionalized – with a very large Islamic religious component within the Free Syrian Army as early as 2012 – and which would have resulted in its annihilation.

Few remember that the people of Suwayda were involved in the 2011 uprising right from the start. As mentioned in our first article, the Suwayda Lawyers’ Guild organized one of the first public demonstrations in March 2011, and as elsewhere in Syria, the Jabal Druze took to the streets in the weeks that followed. To give just a few strong and symbolic examples, let’s recall that one of the main songs of the revolution is “Ya Heif!” (يا حيف – “What a Shame!”), composed and sung by Druze singer Samih Choukheir (Listen by clicking here).

At the beginning of this text, we also mentioned the influence of the Al-Atrash family in the region. Sultan al-Astrash’s daughter, Muntaha al-Atrash, took an early stand against Ba’athist tyranny. In 1991, she publicly tore up a photo of Hafez al-Assad to denounce his involvement with the Coalition in the Iraq war. Saved from prison by her father’s reputation, she joined the Sawaseya Human Rights Organization, becoming its spokeswoman in 2010. At the start of the revolution, she visited rebel areas and publicly called on the Syrian people to join the revolution, before receiving death threats serious enough to convince her to stop appearing in public.

Samih Choukheir

Her daughter Naila al-Atrash, a university drama teacher with close ties to the Syrian Communist Party, was regularly threatened by the regime for her activities, which were deemed subversive. Dismissed in 2001, placed under house arrest in 2008, she took part in the beginning of the 2011 revolt by organizing support groups for people displaced and affected by the conflict, before leaving Syria in 2012. To this day, Naila remains an active supporter of the liberation of Syrians.

Finally, since the assassination of Waheed al-Balous in September 2015, the resistance and revolt against the Assad regime has continued to take shape. It has taken the form of an armed resistance embodied by several popular militias, as mentioned above, but has also largely developed in civil society, with the multiplication of demonstrations and actions that have increased in intensity and regularity since 2020, also as a consequence of the explosion in prices and the cost of living.

To reread in detail the unfolding of these revolts, read our first article published in October 2023: “In Southern Syria, the uprising of Dignity has begun”.

Muntaha al-Atrash

Naila al-Atrash

Hikmat al-Hajari

Hamoud al-Henawi

Youssef Jarboua

It is also necessary to know more about the structure of Druze society to understand that the population is not necessarily subservient to the decisions of a political or spiritual leadership. In Suwayda, religious leadership is embodied by three sheikhs, the “Aql Sheikhs”: Hamoud Al-Henawi, Hikmat Al-Hajari and Youssef Jarboua. The political positions of these three sheikhs are neither identical nor immutable, and their relationship with the Assad regime has varied according to periods and events.

Following the assassination of Waheed al-Balous and the attack on Suwayda by the Islamic State in 2018, the dissensions between the three sheikhs became even more aggravated. Initially neutral or relatively loyal to the Assad regime, they began to become more critical, particularly sheikh Hikmat al-Hajari, who took a clearer stance against the regime and gradually established himself as the charismatic leader of the community.

Editor’s note: The positions taken by the spiritual leadership are not binding on the Druze community, which is predominantly secular and does not follow its commandments as may be the case for other religious communities that accept that religion dictates social and political life. Regularly, Druze sheikhs have publicly declared that they support and follow the community’s choices. More recently, Hikmat al-Hajjari’s cautious yet firm stance on Ahmed al-Sharaa’s transitional government, and in particular on the disarmament of factions, has been much criticized by many people, often ignorant of or hostile to the ways of the Druze community, or even hostile to the Druze in general, out of nationalism or religious zeal. Within the community, his positions are also criticized by supporters of factional disarmament, who see it as the main cause of violence within society and seem to trust (a little too much) in the new Islamist central power not to (re)become a threat to the Druze minority…

The Druze, Israel and the Islamists

This last chapter is essential in view of recent events concerning the Druze communities in Syria and Palestine, and the controversies and rumors that have accompanied them. The two most persistent misconceptions concern the Druze’s supposed loyalty to the Assad regime on the one hand, and their supposed sympathy for Israel on the other. If we have invalidated the first theory in the preceding chapters, it seems to us that we need to add some more recent information than that concerning Kamal Jumblatt’s time to invalidate the second as well.

It should first be pointed out that the Druze communities of Palestine (Mount Carmel and Galilee) were integrated by the Israeli colony in 1948, in the wake of the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians (Nakba). As such, the Palestinian Druze have Israeli citizenship and are subject to compulsory military conscription. Many of them have now accepted this assimilation to the point of supporting the Zionist project and its genocidal policy towards other Palestinians. Their spiritual leader Muafak Tarif is a perfect example of integrationism, cultivating a friendly relationship with the colonial administration and its representatives. He is also quite close to Benyamin Netanyahu.

Muafak Tarif et Benyamin Netanyahu

Location of Druze communities in the Levant

The other Druze community colonized by Israel is that of the Golan Heights, occupied during the Six-Day War in 1967 and officially annexed in 1981. Of the 130,000 Syrians living in the Golan before the invasion, only 25,000 Druze now live on the plateau, in five communes: Majdal Shams, Buq’ata, Mas’ade, Ein Kenya and al-Gager. However, the Druze of the Golan have never accepted assimilation, and almost 80% of them still refuse to take Israeli citizenship.

Israeli leaders persist in trying to win the sympathy of the Golan Druze and never miss an opportunity to claim that they support Zionism, but reality contradicts the propaganda. When, on July 27, 2024, Hezbollah fired a rocket at a soccer field in Majdal Shams, killing 12 children from the community, the opportunistic visits of Benyamin Netanyahu and Bezamel Smotrich to the site and to the funeral were refused by the residents, who booed and branded them murderers.

Finally, when in December 2024 the Israeli army crossed the 1967 border and invaded the Druze villages of Mount Hermon (Jabal al-Sheikh), Zionist as well as anti-Zionist (and campist) propaganda shared the same false information claiming that the residents of Hadar village were in favor of their annexation by Israel. This rumor was initiated by Nidal Hamade, a pro-Hezbollah Lebanese propagandist exiled in France, who posted on his X account a decontextualized video showing a Druze man declaring that he wanted Hadar annexed.

Yet on the same day, representatives of Hadar’s Druze community published a video containing a statement affirming their refusal to be occupied by Israel and denying the false accusations against the Druze.

Unfortunately, rumors often spread more widely than their denials…

For both sides, perpetuating this lie is useful: where Israel has an interest in legitimizing the occupation of Syria’s Arab lands by claiming that its inhabitants want it, the pro-Iranian camp has a clear advantage in keeping alive the myth that Syria’s minorities needed Assad and Hezbollah to protect them from Islamists, otherwise they would turn to Israel. This binarity of analysis feeds on the same campist and feudal logic of thought: “If you don’t place yourself under my protection, then you deserve to be oppressed by my enemy”. And for both sides, the Islamist scarecrow is used to justify the subjugation of civilian populations, insecurity and fear of barbarism (terror) being the colonial powers’ main resources for legitimizing their violations of the conventions and laws of war.

Assad, for his part, has never ceased to present himself as the protector of minorities, using Islamists as pawns to, on the one hand, disrupt the popular revolt against his regime, and, on the other, inflict terror among minorities when and where he needed to in support of his prophecy: “It’s either me, or chaos”.

Hadar residents’ statement, December 13, 2024, Al-Araby TV

In the weeks leading up to the Islamic State’s bloody attack on Suwayda in July 2018 (258 dead and 36 hostages), Assad ostentatiously withdrew all his troops from the region. Then, after the attack, when the population criticized him for not having intervened immediately to block the road to the Islamic State, he responded that it was the fault of the Druze who refused to send their young men into the army. But worst of all, the Islamic State fighters had been transported by bus from Yarmouk (a Palestinian camp on the outskirts of Damascus) to the Suwayda desert a month before the attack as part of a surrender agreement. And, as if that weren’t enough, in November of the same year, a new agreement was signed with the Islamic State resistance pocket in the Yarmouk basin (on the border with Jordan and the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights) for a new humanitarian evacuation to the desert in exchange for the release of the Druze hostages taken by the Islamic State after their attack on Suwayda. It should be noted that these two agreements between the regime and the EI were organized under the patronage of the Russians, who had at the same time made a commitment to Israel to keep any threat from Islamists, including Hezbollah, away from its border.

We discuss the attack on Suwayda by the Islamic State in more detail in our first article published in October 2023: “In Southern Syria, the uprising of Dignity has begun“

And to conclude: As Islamists have often been the useful idiots of imperialism on all sides, it should come as no surprise that the Druze of Suwayda are in no hurry to hand over their weapons to the new power in Damascus, since Ahmad al-Sharaa has been the representative of the two Islamist movements, DAESH and Jabhat Al-Nosra, which have violently attacked the Druze over the past decade. And that certainly doesn’t make them Israel’s allies, whatever supporters of Iran and Israel may think.